Ford Motor Co.’s slick, new electric sleigh, the Mustang Mach-E, can be plugged into a standard electrical outlet like a 4,500-pound toaster. It’s a pragmatic trick, but not much more than that. It takes the machine 10 hours to draw enough juice to travel 30 miles. Anyone riding the silent pony further than the local coffee shop will probably need an upgraded outlet.

Americans will need 26 million new charging outlets installed at their homes and apartment buildings over the next decade, requiring some $39 billion in investments, if the country’s auto industry is going to go entirely electric by 2035, according to a new study by Atlas Public Policy, a Washington D.C.-based research firm. The findings highlight a reality we’re already too familiar with: range anxiety has given way to charge anxiety, as electric-curious drivers no longer wonder how far they can go, but if there will be working, relatively quick options to “fill up” once they arrive. While much has been made about the lack of charge points in rural states, the problem begins and ends at home.

“Convenience is going to be the next big hurdle for electric vehicles, beyond these early adopters who think it’s cool to hang around a charging station for an hour and talk about their vehicles,” said Lucy McKenzie, the lead author of the Atlas study. “And the home-charging challenge is still a significant hurdle.”

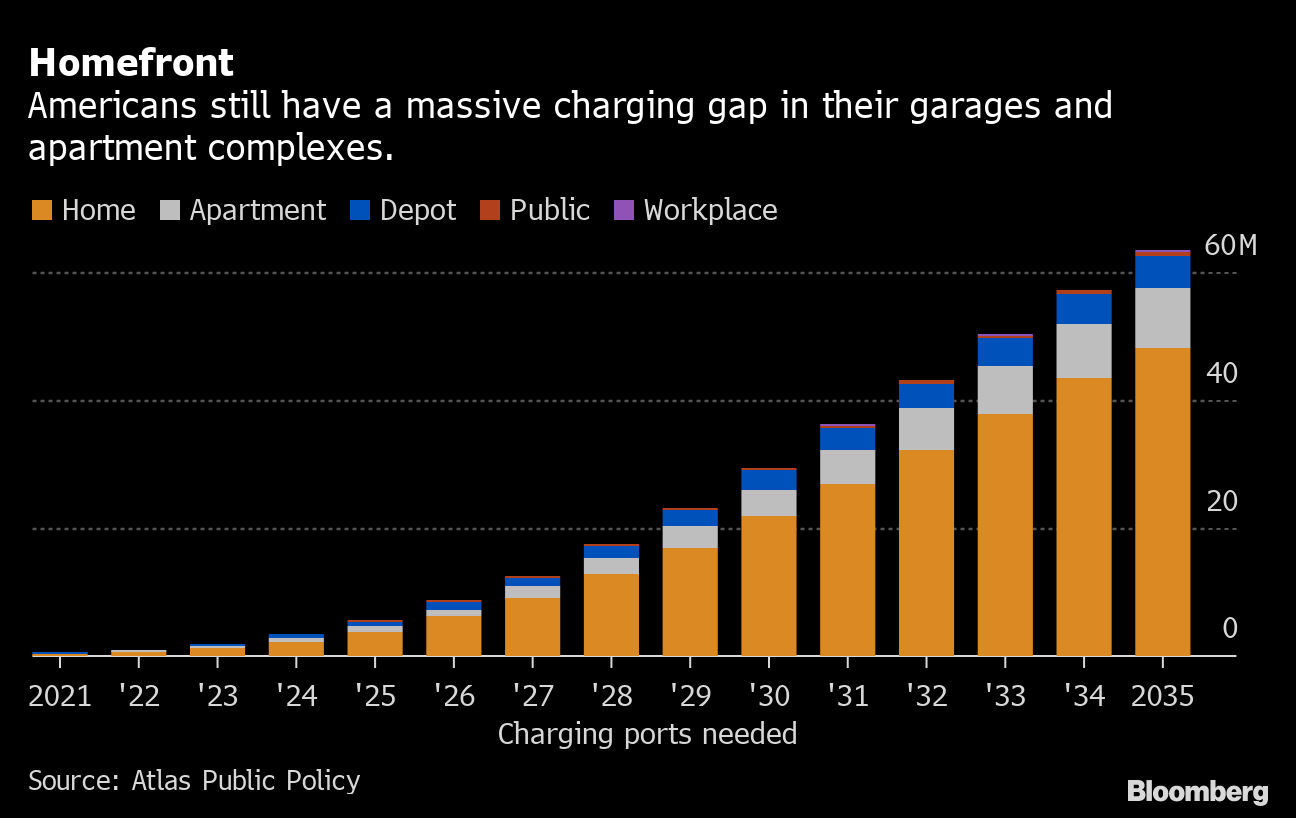

Homefront

Americans still have a massive charging gap in their garages and apartment complexes.

Source: Atlas Public Policy

A lot of U.S. homes already have slightly faster charging options — known as “Level 2” in EV-speak — it’s just that they are in the laundry room, powering the washing machine and dryer. Installing one in a private garage costs between $1,000 and $2,500, according to Atlas. For much of the Tesla crowd, that may not be a non-starter, but for the masses stretching to buy a new car, it could be a reason for not ditching gas engines entirely. The added expense could be one reason why General Motors is covering the cost of home chargers for the first wave of people buying its 2022 Bolt electric vehicles.

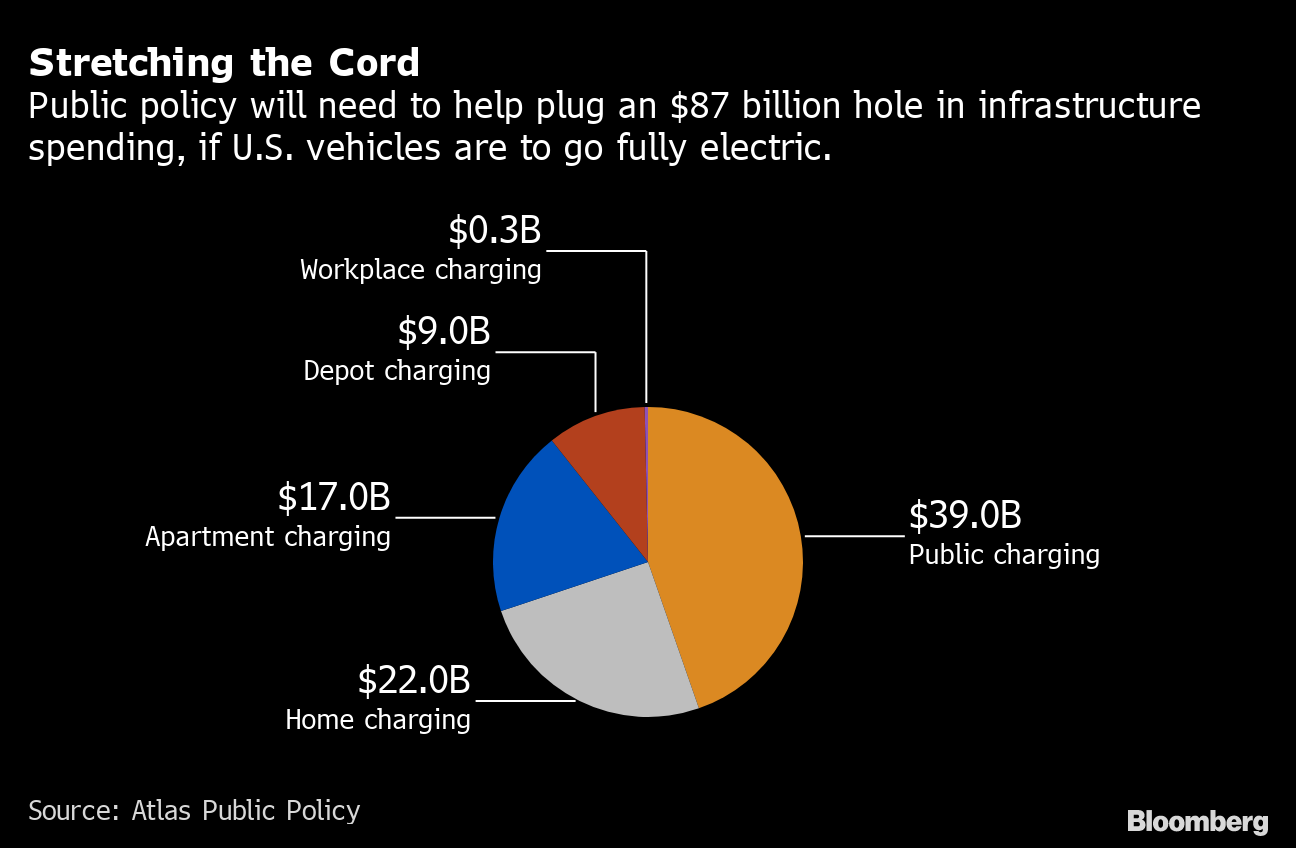

Ironically, the home-charging hurdle is almost as high as that of public charging, according to the Atlas analysts. To fully flip the switch to electric vehicles, the country will need another $39 billion in infrastructure investments by 2031, enough for 495,000 outlets in public stations and workplaces, Atlas reckons.

Stretching the Cord

Public policy will need to help plug an $87 billion hole in infrastructure spending, if U.S. vehicles are to go fully electric.

Source: Atlas Public Policy

Here though, a tide of government funds may cover a lot of ground. The Biden Administration has proposed $174 billion in spending for electric vehicles; about $15 billion of that is reportedly earmarked for charging stations, 500,000 in all. If the Atlas study proves accurate, the investment won’t be quite enough, but the private sector is sure to cover a lot of new cords as well. Some $4.5 billion in charging commitments have been made by state governments, utilities and Electrify America, the charging network spun out of Volkswagen’s Dieselgate settlement.

Charging in the EV ecosystem is a chicken-and-egg problem. Companies won’t build chargers without electric vehicles; customers won’t buy electric vehicles without chargers. “The charging companies are still really reactive to the market,” McKenzie said. “They’re not in front.” The Atlas study suggests that subsidies are the best way to break that staring contest and Team Biden seems to agree.

What’s interesting, however, is how all these investment figures are correlated. Any additional federal spending on EV infrastructure is going to embolden charging networks and automakers alike, strengthening the sort of flywheel effect that we’ve seen a little of lately. Indeed, Biden’s infrastructure plan has buoyed for-profit charging companies like ChargePoint Holdings Inc. And every bold EV announcement from Detroit or Silicon Valley seems to spark another elsewhere — the entire hurdy-gurdy market accelerating quickly on that most precious fuel stock: FOMO.