While the core mission of power networks has long been to keep the lights on, grid operators now face the challenge of keeping wheels rolling, as the decarbonisation of transport places more demand on electricity supplies.

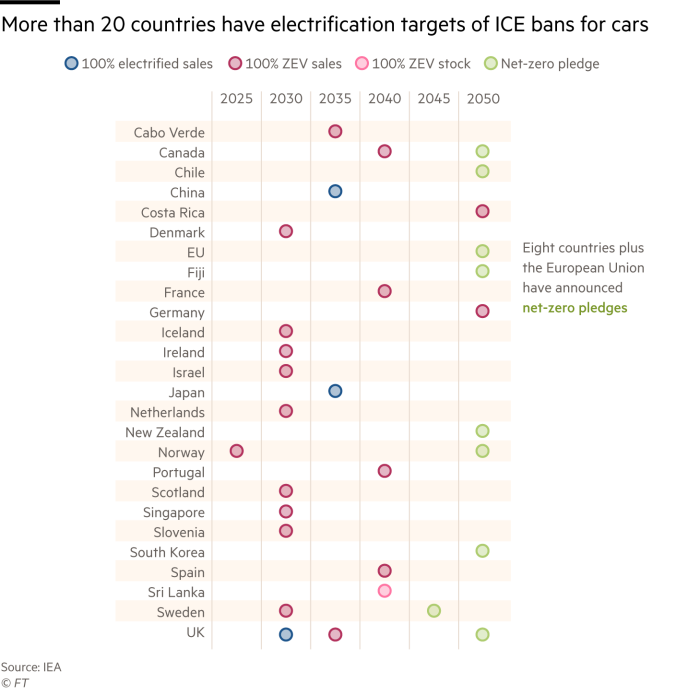

Last year, the number of electric vehicles rose more than 40 per cent year-on-year to surpass 10m globally, according to the International Energy Agency. While that represents just 1 per cent of the total number of vehicles, electric car sales are accelerating: the IEA suggests that, under current policies to reduce carbon emissions, the world’s fleet of electric vehicles could expand to 145m by 2030.

Experts agree that the path to meeting “net zero” targets will require the widespread adoption of zero-emission vehicles, as well as re-engineering the way cleaner energy is delivered to the transport fleet.

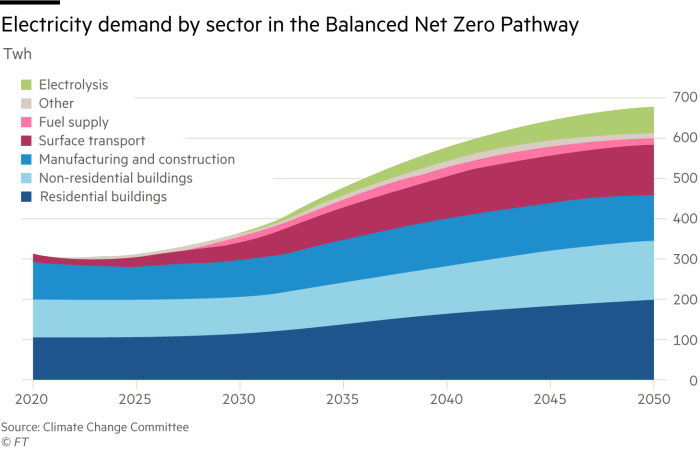

“Cars are [both] a threat and an opportunity to the grid and how to help the energy transition,” says Graeme Cooper, director of transport decarbonisation at the UK’s National Grid. “By the time we get to net zero [in 2050], we will need twice as much electrical energy compared with what we have today,” he says.

A study by the UK’s Climate Change Committee predicts that the increased electrification of the country’s economy, including the widespread adoption of EVs, could lead to a doubling of annual demand, from 300 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2019 to 610 TWh by 2050.

David Joffe, head of carbon budgets at the advisory body, says although technological improvements are driving down the cost of EVs, it is vital to ensure that “charging infrastructure is where it needs to be” to encourage uptake.

The prize is the decarbonisation of road transport, which remains the single biggest source of UK greenhouse gas emissions, ahead of power generation, the heating of buildings, and general industrial use, says Joffe.

The good news, according to Cooper, is that the rapid growth of renewable energy sources — alongside the early planning of power distribution upgrades and the adoption of digitised demand management systems for vehicle charging — should enable a green transport revolution. And keep the lights on, as well.

“The grid has been evolving — the grid is the cleanest it has ever been,” he says. But the key will be encouraging vehicle charging when demand is low, to avoid spikes in demand that require the deployment of polluting hydrocarbon-fuelled power stations.

Cooper believes the development of smart meters and charging systems, combined with tariffs that encourage consumers to use energy during low-demand periods, can help “put the cleanest and cheapest power into cars and tumble dryers”. It can also restrain consumers from “using energy when the grid is strained and when generation is dirtiest”.

Miguel Stilwell de Andrade, chief executive of EDP, the Portuguese energy group, points to forecasts that EVs will account for 2-3 per cent of global electricity demand by 2030, though higher uptake in Europe could see the level reach 5 per cent on the continent. By 2040, the figures could grow to 9 per cent globally and 16 per cent in Europe, Stilwell de Andrade says.

This growth could strain the power system, he adds. “If unmanaged, as EV usage gains ground, the charging of EVs could potentially more than double the power intake on specific local grids, requiring significant investments in grids as well as supply capacity.”

However, he concurs that this increase in demand can be mitigated through smart refuelling technology. “Fortunately, these technologies are becoming increasingly available, and their adoption should speed up in the coming years,” he says.

Europe overtook China for sales of EVs in 2020, though China still has the largest fleet and has continued to invest in expanding its recharging network, according to an IEA report.

The US, in comparison, remains a laggard in terms of sales and federal government support for the adoption of EVs. But companies and policymakers are waiting for commitments from the new White House administration on encouraging a switch away from internal combustion engines.

Car manufacturers, local utilities and individual states are also taking the lead in encouraging cuts to “well-to-wheel” emissions, as the new US president Joe Biden plots a re-engagement with the Paris climate agreement.

In September, California said it would unilaterally ban the sale of new cars and passenger trucks fuelled by fossil fuels by 2035, while Massachusetts has committed to following suit.

Matthew Cloud, who develops National Grid’s EV strategy across its US territories, says there is a need to “proactively install infrastructure and incorporate renewable energy capacity” into the local grids, to encourage the uptake of EVs and ensure that state policy objectives are met.

More charging points, along with time-of-use tariffs and smart charging systems, will be vital to ensuring grids do not act as a brake on EV adoption, he adds. “There will need to be more investment — the question is to what extent.”