If smugness could be bottled and burned, East Coast drivers would have had no problems this week.

The stuff was spewing out of Teslas, Nissan Leafs and every other electric vehicle silently zooming past dry gas pumps and frantic drivers filling all manner of receptacles with fast-dwindling fuel. When hoarders turned to plastic bags, the righteousness of the clean, green observers, no doubt, hit the redline.

“It’s certainly an opportune time to be an EV driver,” Clemson University economist Matthew Lewis said from his home in northwest South Carolina. “Around here, there’s no gas at all.”

Gas stations are slowly refilling their reservoirs this weekend, but will the Colonial Pipeline debacle — a computer hack that shut down the country’s largest gas conduit and triggered panic hoarding that exacerbated shortages — spur a wave of electric vehicle sales? The short answer, according to economists like Lewis: probably not. But there is a big “but” to consider.

Even as some gas stations ran dry across the Southeast, the average U.S. price per gallon remains far below where it hovered from 2011 to 2014.

Photographer: Kena Betancur/AFP/Getty Images

Historically, gasoline isn’t a very elastic product, which is to say drivers aren’t very sensitive to swings in its price — at least not sensitive enough to change their driving habits or buy a greener vehicle. In fact, there’s evidence that U.S. drivers have grown less sensitive to increasing gas prices in recent years. A 2006 study from University of California economists found a 10-fold decrease in gas elasticity between the late 1970s and early 2000s. The authors cited an increase in suburban development and commuting, coupled with a decline in public transportation; more efficient vehicles may have also played a part, the economists posited.

When oil prices dropped in 2014, sales of hybrid vehicles dipped as well, suggesting a weak correlation, according to BloombergNEF. However, the adoption rate of fully electric vehicles didn’t deviate, it remained steady, suggesting the Tesla crowd was making purchase decisions based on the environment and personal choice rather than monthly gas bills. That’s not surprising given the average price point of electric vehicles at the time; nearly the entire product category fell in the “luxury” segment.

Inelastic

Sales of electric vehicles have plodded along in recent years, despite a swoon in gas prices.

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence

For nearly any product, demand elasticity depends largely on two things: duration and alternatives. For the former, people don’t dial down demand unless the price hike is expected to drag on. That seems to be the case this week: Even as gas stations ran dry, prices only climbed 4.8% in the past two weeks. At $3.04 a gallon, the average U.S. price remains far below where it hovered from 2011 to 2014.

A bullish economy — particularly in a tight labor market — tends to trump any penny pinching at the pump. Generally, when we are working, we are driving. When we are earning more, we are buying bigger, less-efficient vehicles, and driving more.

Electric miles can run dry as well. Frank Wolak, a Stanford economist, noted that widespread power outages are far more common today than pipeline shutdowns. Indeed, energy stewards across the U.S. West are warning about a summer of blackouts, as extreme heat stresses utilities shutting down dirty plants and shifting to wind and solar power generation.

What has changed is the second function in the elasticity equation: alternatives. With the most price elastic products, consumers tend to have other options. Beef is a good example; if steak gets spendy, people turn to hamburgers or chicken. As for vehicles, there have never been as many alternatives to gasoline as there are at the moment and they’ve never been as affordable. In the oil crisis of the 1970s, the alternative to a long line at the pump was a bus pass; today, it’s a Nissan Leaf, which can be had new for $31,670, before any applicable federal and state rebates, or used for pennies on the dollar.

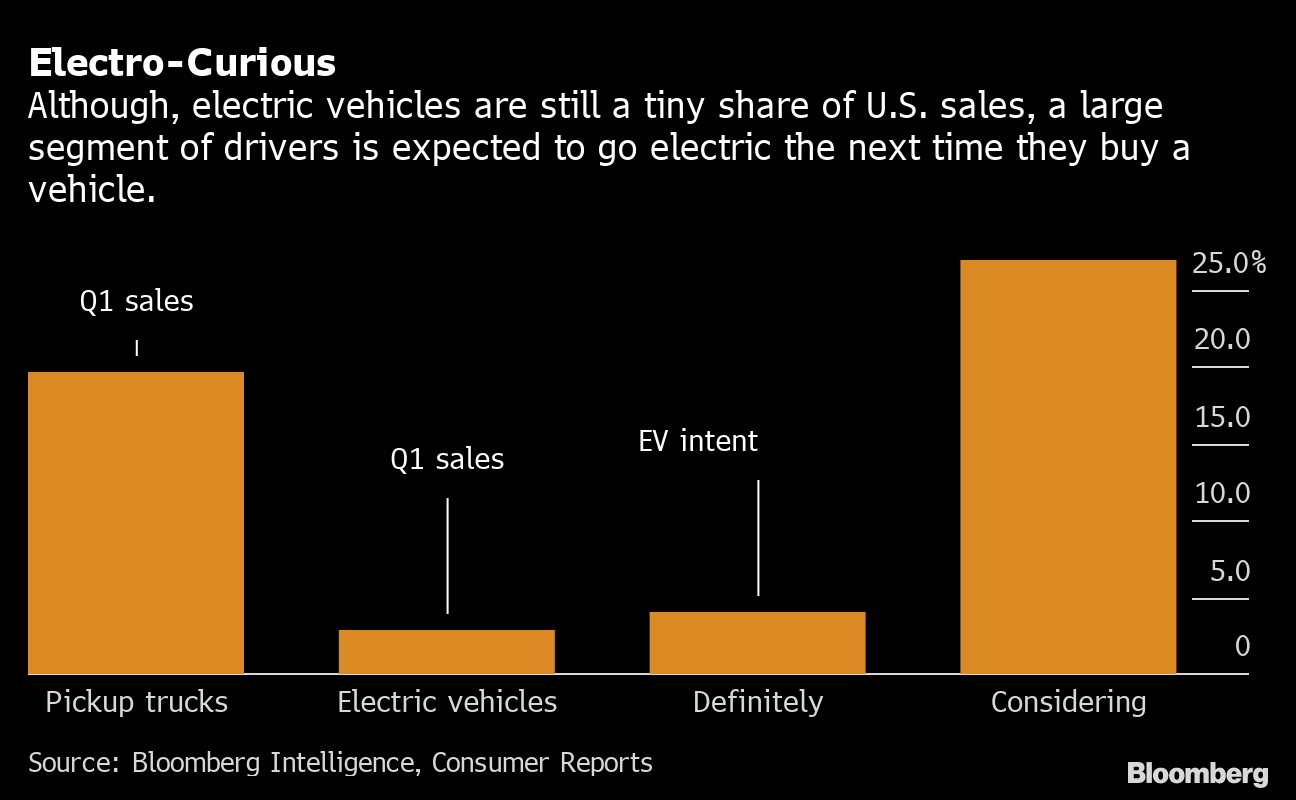

Electro-Curious

Although, electric vehicles are still a tiny share of U.S. sales, a large segment of drivers is expected to go electric the next time they buy a vehicle.

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence, Consumer Reports

What’s more, potential car buyers have never been so EV-curious. Some 4% of U.S. drivers “definitely” plan to buy an electric vehicle for their next purchase and another 27% are strongly considering one, according to a December survey by Consumer Reports.

Jonathan Levy, chief commercial officer at charging network EVgo, believes the pipeline drama accelerates the tailwinds for EV adoption. Cleaner air that came from COVID lockdowns was another recent “check in the ‘pro’ column” for prospective electric buyers,” Levy said.

Even so, Nick Nigro, executive director of Atlas Public Policy, doesn’t expect any immediate green shoots. But he said the pipeline glitch “plants more seeds” of potential EV drivers. “If we end up in a place this summer where the wild swings in the price of oil point upwards,” Nigro said, “you can expect a compounding effect.”

“This is a very unique event,” Clemson’s Lewis said of this week’s gas crisis. “There are a lot more people entertaining the idea who are about to get a lot more options. For people like that, this is a new piece of information.”