COLUMBUS, Ohio — Seven years since buying his first Tesla, Gregory Schenk, 61, said the purchase was the best decision he’s made, but it was only a viable option because of the car manufacturer’s robust charging network and his ability to install a plug at home.

What You Need To Know

- Access to charging can make or break the decision to go electric

- There are about 45,000 electric charging stations in the U.S. currently

- That number will need to rise to support projected growth in the market

“When I talk to people that have never done it, charging is one of their biggest fears,” Schenk said. “I mean, I think it’s Tesla and everyone else. Mercedes is coming out with an electric car, and I drove Mercedes for 25 years — they’re awesome cars, but there’s no charging network. To me, that’s the million dollar question for all these other brands, are they going to do it?”

Schenk has been driving a Model X for the last 18 months.

As electric vehicles become more efficient and affordable, cities, companies and elected officials are working on the public charging infrastructure to support projected growth in the market. Advocates view charging as the critical piece to electric vehicle adoption.

Brendan Kelley of the nonprofit Clean Fuels Ohio said more than 80% of electric vehicle charging currently happens at home, but that’s not necessarily an option for those who are renters or live in residential buildings.

Kelley, who is the director of the nonprofit’s Drive Electric Ohio initiative, said there’s a need for continued expansion of public charging options at places like grocery stores, parks and malls, as well as installations at workplaces and in multi-family dwelling parking areas.

“We’re on sort of a cusp between people who control parking structures considering EV charging an amenity to it becoming a necessity,” he said. “Yes, there’s been a lot of progress, and yes, there’s still more work that needs to be done.”

According to the Department of Energy, there are about 45,000 public charging station locations in the U.S. and about 110,000 total ports. Only about 5,500 of those are DC Fast chargers, which can get drivers back on the road in about 15 to 45 minutes, depending on the vehicle.

President Joe Biden, as part of his climate goals, has stated a target for 50% of new vehicles to be electric by 2030, and his administration is seeking funding in infrastructure negotiations for growth to 500,000 chargers. The administration is stressing the importance of addressing equity gaps in access to charging.

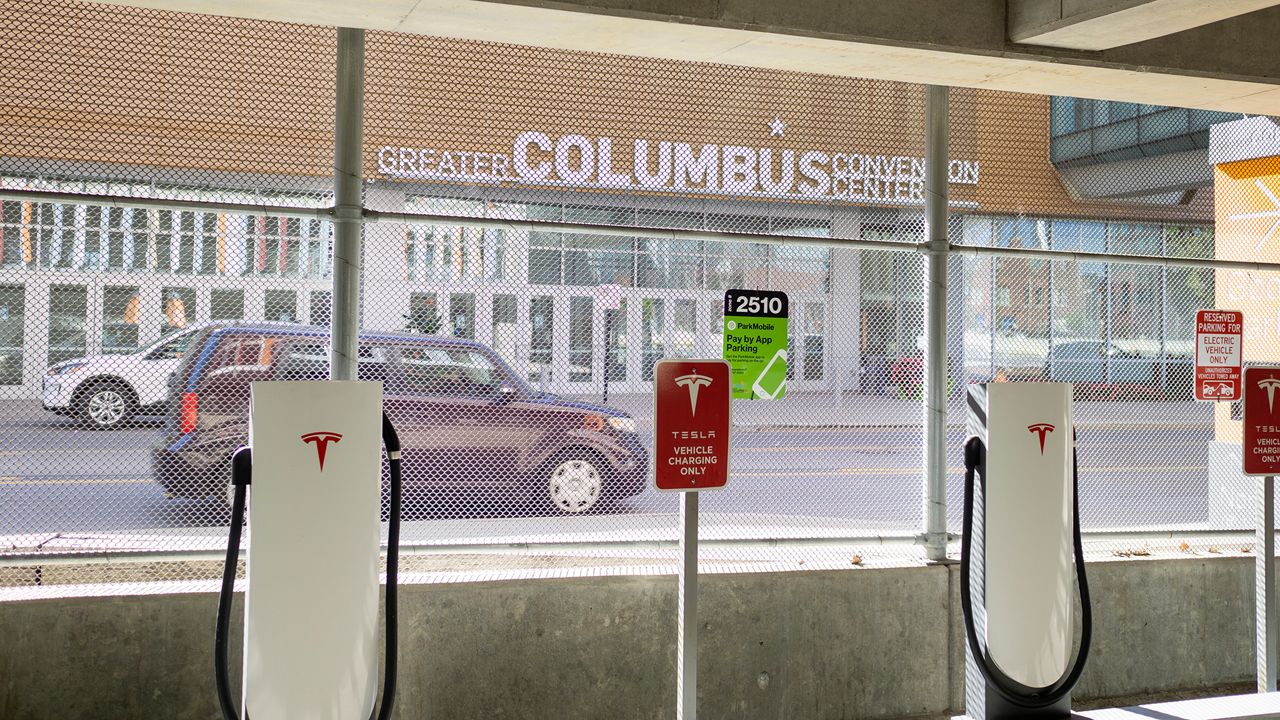

The Greater Columbus Convention Center has 20 electric chargers installed by Tesla. (Spectrum News, Pete Grieve)

Installing chargers in disadvantaged neighborhoods is the most urgent area that needs to be addressed, Kelley said, but another solution is expanding electric-powered public transit to reduce pollution in communities where the switch to electric vehicles is likely to be more prolonged.

In the Columbus area, a $10 million grant from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation and a significant statewide investment by American Electric Power for public charging has helped the region move in the right direction toward increased adoption of electric vehicles, Kelley said.

But only 29,500 electric vehicles are registered in the state, compared to millions of gas-powered vehicles on the road, Kelley said.

In addition to better charging infrastructure, he said policy will need to support electric vehicle adoption if those numbers are to improve. Kelley said that could include incentives for vehicle purchases and for manufacturing, like factory retooling incentives.

“Automakers are making decisions about where their facilities are going to be based that produce EVs, and they’re going to be investing $330 billion globally between now and 2025,” Kelley said. “That’s a lot of money very quickly. These production siting decisions are being made right now, and investment follows policy.”

Members of Congress are discussing additional incentives for buying electric vehicles. House Democrats have called for tax credits of up to $12,500, but negotiations are ongoing.

Schenk said barriers like a $200 annual registration fee in Ohio for electric vehicles need to go.

“They should be paying us,” he said. “Here we are saving everybody this and that — no noise, no pollution, and they still want the extra road tax. I think that’s just zero common sense — like most government stuff is, unfortunately.”