It took Google eight years to reach $10 billion in sales, the fastest ever for a U.S. startup. In the current SPAC frenzy, a spate of electric-vehicle companies planning listings are vowing to beat its record—in some cases by several years.

Among the most ambitious are luxury-car maker Faraday Future, U.K.-based electric-van and bus maker Arrival Group, and auto maker

Fisker Inc.

Each has disclosed plans to surpass the $10 billion revenue mark within three years of launching sales and production.

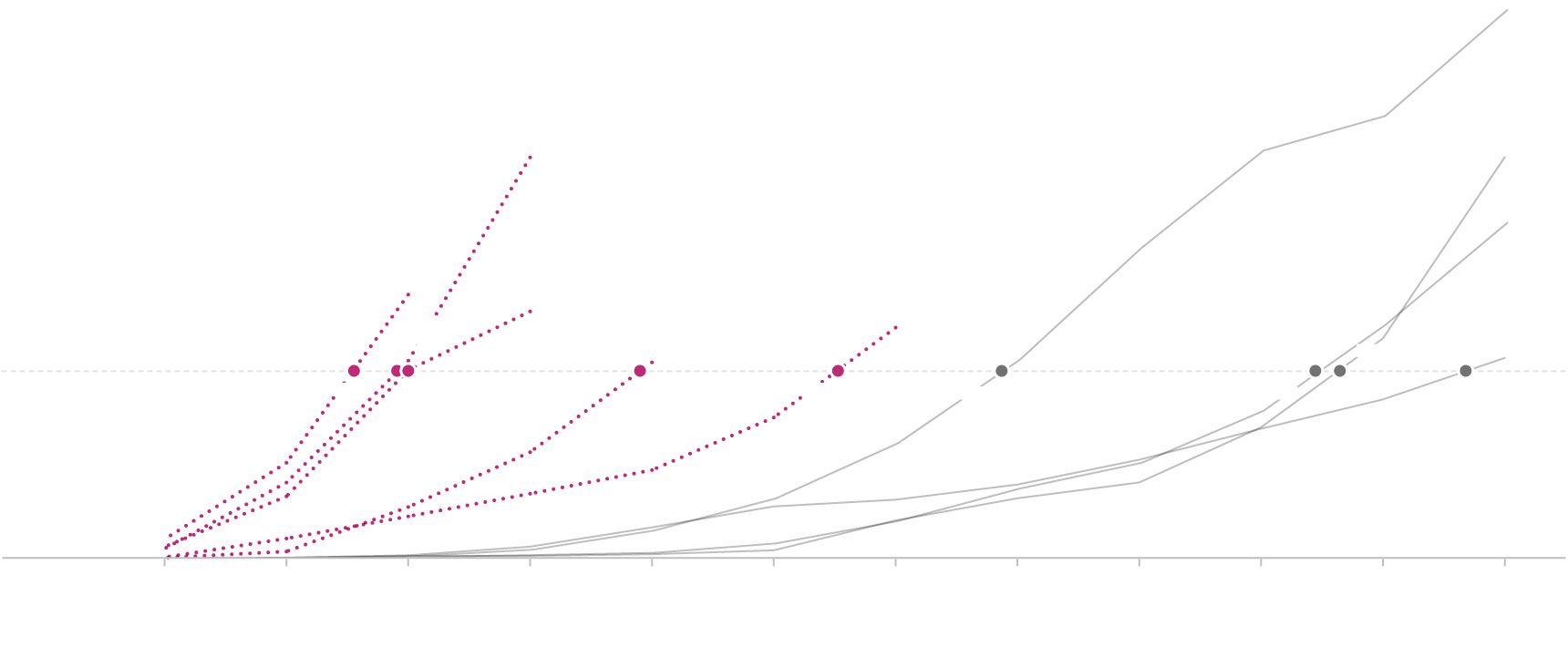

Projected revenues for electric-vehicle companies recently publicly listed through SPACs

Annual revenue:

$10 billion

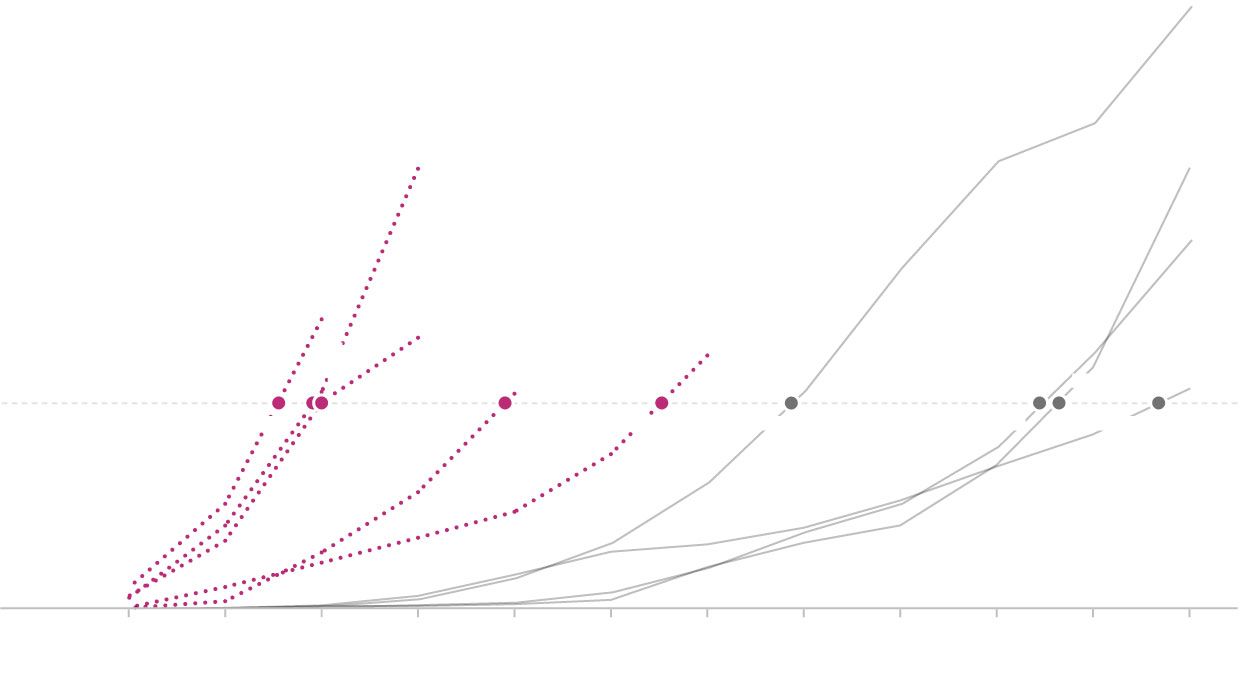

Projected revenues for electric-vehicle companies recently publicly listed through SPACs

Annual revenue:

$10 billion

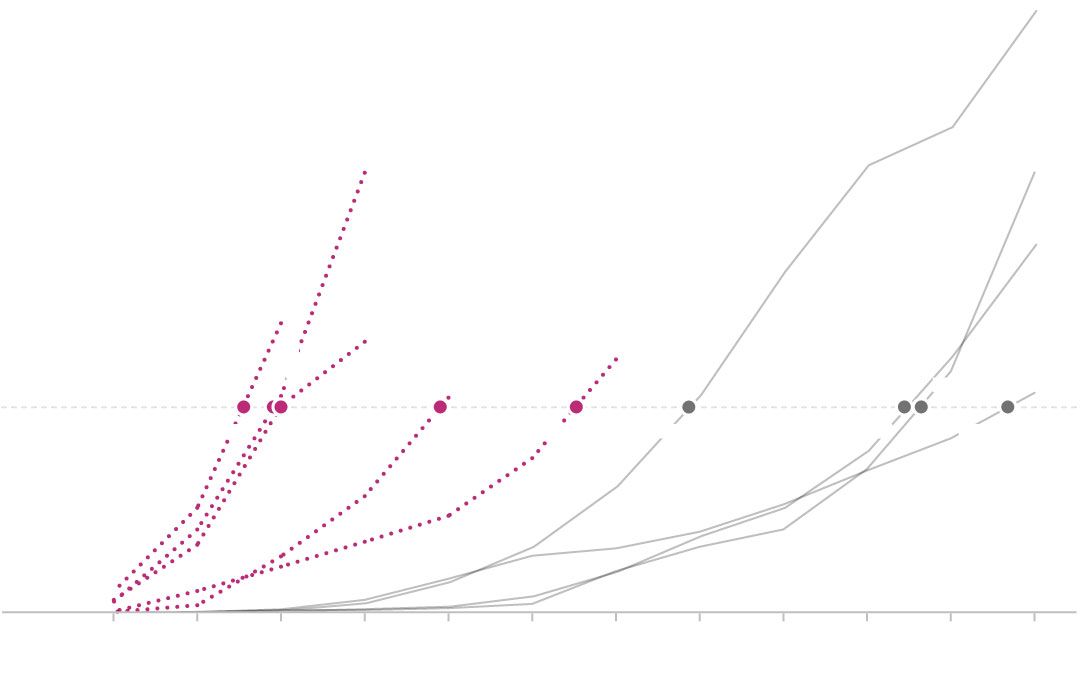

Projected revenues for electric-vehicle companies recently publicly listed through SPACs

Annual revenue:

$10 billion

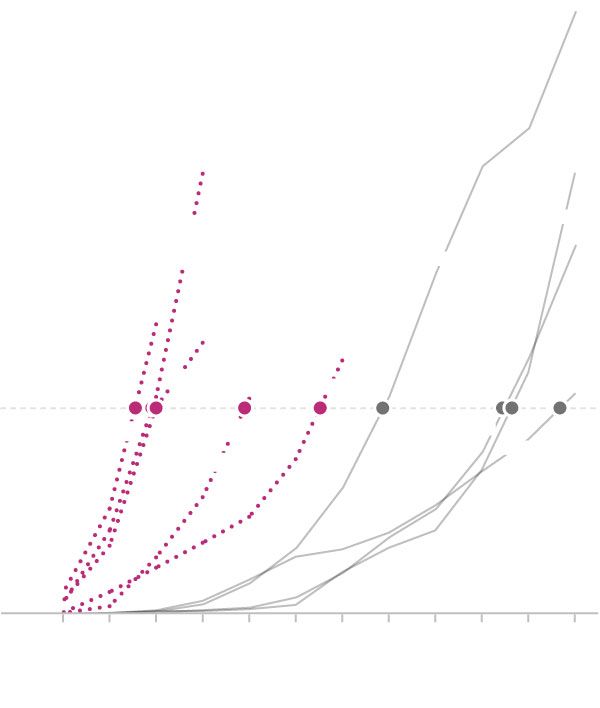

Projected revenues for electric-vehicle companies recently publicly listed through SPACs

Annual

revenue:

$10 billion

Alphabet Inc.’s

Google was followed by

Uber Technologies Inc.,

which hit that mark within nine years of its first revenue, and then by

Facebook Inc.

and auto maker

Tesla Inc.,

which surpassed $10 billion in revenue within 11 years of first generating sales, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data provided by research firm Morningstar Inc.

Two other companies, Israel-based electric-vehicle component supplier Ree Automotive Ltd. and Archer Aviation Inc., which intends to make an electric helicopter-like vehicle, plan to hit the mark within seven years of launching their products. Those two—like Faraday, Arrival and Fisker—have completed listings or are in the process of going public by merging with special-purpose acquisition companies, or SPACs.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How long do you think the SPAC boom will continue, and why? Join the conversation below.

The forecasts for record-setting growth illustrate the extent of the fervor for electric-vehicle startups, particularly for those going public by merging with SPACs, which are shell firms that list on a stock exchange with the sole purpose of acquiring a private company to take it public. More than 10 electric-vehicle or battery companies that struck deals with SPACs have been valued in the billions of dollars before producing any revenue, as amateur traders and many traditional investors have flocked to the buzzy sector.

Backers say a shift away from gas-powered cars should open doors for new brands. Much of the enthusiasm, investors say, is also because of the glow from electric-vehicle maker Tesla’s $665 billion market capitalization. While its stock has fallen in recent months, Tesla shares soared more than eightfold in 2020.

Startups hoping to replicate Tesla’s success have been choosing SPACs—a speedier alternative to a traditional initial public offering, with looser regulatory requirements—and releasing charts to investors showing how their plans call for them to grow faster than Tesla did. Those projections, which regulations strongly discourage in IPOs, are another important factor in how investors value the emerging companies. Expectations of growth tend to lead to higher valuations.

The extraordinary aspirations and the lofty valuations have caused some analysts to say the forecasts are unrealistic.

Pavel Molchanov,

an analyst at Raymond James who covers the clean-tech sector, said all of these projections need a “haircut.”

Even with governments around the globe pushing consumers away from gasoliine-powered cars, there is set to be a wave of new electric cars that could overwhelm consumers, Mr. Molchanov said. “I think there is too much optimism about demand,” he said.

The companies and their backers say they face a far different market than the fastest-growing companies of yesteryear. Even the best tech companies can take a while to become household names, but cars and trucks have such high price tags that it takes relatively few buyers to reach sales figures in the billions, they say.

Further, they say, the electric-vehicle market has matured significantly since Tesla was beginning, opening up the startups—many of which have raised sizable chunks of funding early in their lives—to a wealth of suppliers that can make production easier.

Simon Sproule,

a spokesman for Los Angeles-based Fisker, said the company’s plan to rely on third-party manufacturers to build its cars will allow it to increase manufacturing far faster than Tesla did, while its initial vehicle is aimed more at the mass market.

“The addressable market we’re going into is much, much bigger” than Tesla’s, he said.

A Fisker electric sport-utility vehicle on display last year at an event in Las Vegas.

Photo:

Bridget Bennett/Bloomberg News

Arrival, which plans to go from no revenue this year to $14 billion in 2024 by selling electric buses and delivery vans, is betting that operators of large fleets of the vehicles will quickly transition to electric amid broader government efforts to reduce emissions.

“We believe this is an inflection point for rapid adoption of millions of electric vehicles,” said Avinash Rugoobur, Arrival’s president.

Others with forecasts for rapid growth include Joby Aviation, which estimates it will have $20 billion in revenue in about 10 years, and electric-car maker Lucid Motors Inc., which plans to reach $22 billion in sales by 2026. Lucid has already generated some revenue from battery sales and is launching its first car this year.

Before the companies deal with demand, some investors say a stumbling block could come from manufacturing, a particularly challenging endeavor given the complex auto supply chain.

Gavin Baker, a large investor in Tesla in the early 2010s when he was portfolio manager at mutual-fund company Fidelity Investments, said it is unlikely the companies “are going to be able to ramp at a rate two-to-three times faster than Tesla did” after it launched its Model S.

“It is easy to make PowerPoint slides; it’s relatively easy to make a few prototypes that look good and drive well,” said Mr. Baker, now the chief investment officer at Atreides Management LP. “It’s mass producing high-quality, reliable cars that’s hard.”

Startups that publicly list through SPACs face different regulations around forecasts than IPOs because the deals are officially mergers, not public offerings that face a higher level of scrutiny from regulators.

This dichotomy has raised concerns among some venture capitalists and others who say the inherently speculative forecasts can contribute to hype around a company that it wouldn’t receive in an IPO.

“The real problem here is it’s a regulatory arbitrage—it’s a loophole,” said

Robert Jackson,

a former commissioner with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and a professor at New York University’s law school. He said regulators should make it more difficult for companies to publicly offer such projections.

Some SPAC managers have hailed the ability to provide projections, saying they help startups communicate their vision to investors.

Regulators are paying attention. Officials from the SEC last week indicated they are stepping up scrutiny of the SPAC market.

Write to Eliot Brown at eliot.brown@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8