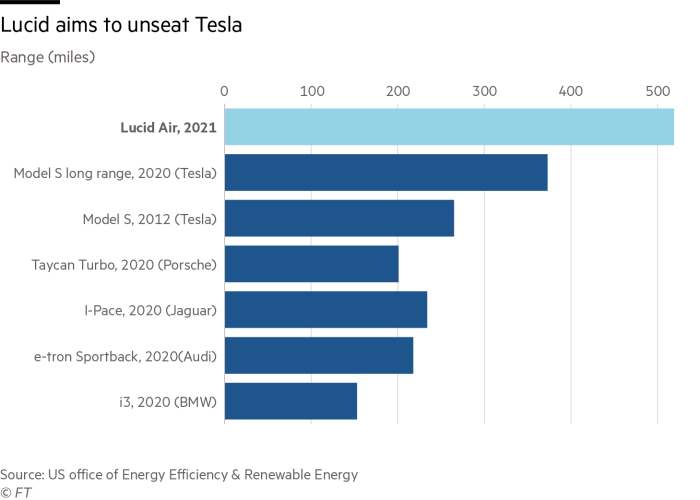

Two years ago Tesla chief executive Elon Musk proudly claimed there was still no battery car that could compete with the Model S he launched in 2012.

At the time, it was true — and even models from Porsche and Jaguar in 2020 failed to match the specs of his eight-year-old electric vehicle. “Still waiting,” Musk quipped.

Lucid Motors claims the wait is nearly over.

The Lucid Air, which is set to begin production later this year, boasts a range of 500 miles, twice the 2012 Tesla range and a quarter higher than any current Tesla, plus a recharging system that would replenish hundreds of miles within minutes.

The company, backed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, wants to emulate not only Tesla’s battery-stretching performance in its cars, but also the stock market acceleration that has seen it catapulted to become one of the world’s most valuable companies.

This week, the business filed for a $24bn listing through a special purpose acquisition company, in the largest Spac deal to date.

“We’re in a fantastic position. We raised more than we needed to and we have long-term financial partners who may commit more,” Peter Rawlinson, Lucid’s chief executive, told the Financial Times.

But the announcement of the stock market listing came with news of a delay to the launch of the Air, originally planned for spring. It highlighted, for anyone perhaps unfamiliar with Tesla’s own meandering journey to profitability, how timelines can slip in the electric-car business.

Lucid was founded as long ago as 2007, as a battery technology company called Atieva, when a group of Musk’s employees defected, in the belief that Tesla’s plan to build an actual car, rather than supplying batteries and drivetrains, was the wrong approach.

“It took the team until 2013 to recognise what Tesla recognised,” said Rawlinson, chief engineer for the Model S, who was brought aboard that year to design a “post-luxury” vehicle.

Despite the pivot to carmaking, Lucid’s claim to fame so far comes from battery tech — specifically for the racetrack. It is the designer and manufacturer of battery packs for all 24 vehicles in Formula E, the electric racing championship founded in 2014.

In its early years, Formula E attracted plenty of jokes. Drivers had to take mandatory pit stops to swap vehicles midway through the race because they were unable to complete the circuit on a single charge.

“Formula E was created to exemplify the potential of electrification but all it did was exemplify its limitations,” Rawlinson said.

Lucid competed to supply better technology in 2016, won the contract, and helped redefine the race as the electric counterpart to Formula One, attracting Porsche and Mercedes to compete.

The partnership has created only modest revenue, but it was the proving ground for Lucid to differentiate itself from rivals, attract talent, and eventually led to a critical $1bn investment in 2018 from Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which remains Lucid’s majority owner.

“Everyone thought I was nuts but it saved the company,” Rawlinson said.

The agreement to merge Lucid with Churchill Capital IV, one of several Spacs set up by dealmaker Michael Klein, came as little surprise.

Rumours had been swirling for weeks about a potential deal and Klein has a long history with Saudi Arabia — whose sovereign wealth fund will remain majority owner of the electric-car maker — as one of the kingdom’s key advisers.

A heady mix of two of Wall Street’s favourite trends — Spacs and electric vehicle upstarts with plenty of promises but no revenue — sent shares in Klein’s Spac up almost 500 per cent prior to the deal’s announcement. But when the press release landed, it became clear that some of the key players had got a cheap deal.

While shares in Churchill were trading as high as $60, Churchill and institutional backers were handed Lucid shares at $10 or $15 a piece. This unusual way of structuring the transaction effectively gave the company three different valuations ranging from $12bn to $64bn.

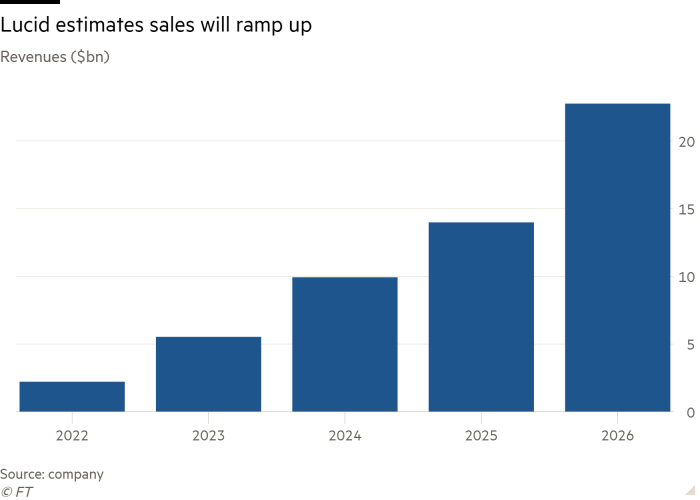

Like so many businesses that use reverse mergers, the company is months away from any meaningful revenues, and its plans seem to involve burning cash at a prodigious rate for years to come.

Forecasts from its investor presentation include burning $7.5bn between 2022 and 2024, before finally generating $321m of cash in 2025, then $1.5bn in 2026.

Revenues will ramp up to $2.2bn next year, quadrupling to $9.9bn by 2024, then climbing to nearly $23bn by 2026, the presentation states, implying profits from 2024. Needless to say, these numbers are speculative.

Production has been pushed back into the second half of this year, the company disclosed in the same document.

“All car programmes when several months out, there are part-quality issues,” Rawlinson said. “If it was perfect, we’d have it in production today.”

Even among analysts who consider Lucid best of breed among the Tesla followers, there is widespread scepticism that Lucid can fulfil its pledge of going from zero deliveries today to 50,000 by 2023 and 1m by 2030.

“Going from PowerPoint to mass scale production in the millions of units is extremely difficult,” said Neil Campling, tech analyst at Mirabaud Securities. “We’ve been here many times before, where the proof of concept has not led to actual commercial viability and scale.”

Rawlinson said the Spac deal bought the company breathing space to tackle quality issues, bringing in $4.4bn after fees that means it will not need to raise again until early 2023 in order to fund its second vehicle, the Gravity SUV.

Rawlinson has little hesitation inviting comparisons to Tesla, suggesting that Lucid can replicate its success and outperform any of the established competitors such as Mercedes and Jaguar.

“There’s only one company that’s got world-class tech out there and it’s Tesla. No one else is even close,” he said.

But while Lucid has the advantage of learning from Tesla’s successes and failures, the group will also have to face a flurry of new models from traditional manufacturers, in an onslaught analysts are calling “the Empire Strikes Back”.

Arndt Ellinghorst, auto analyst at Bernstein, expects up to 30m electric vehicles will be produced annually by 2030.

“There’s no first-mover advantage any more,” he said. “There’s very little tech differentiation in the battery or software left, so all this really comes down to is brand equity and being able to scale fast — manufacturing, service, the whole ecosystem of a car. That’s not easy.”

Rawlinson dismissed the thesis, pointing out that the early efforts by established names such as Audi and Jaguar have all fallen short, and claiming that none of the big carmakers currently poses a threat.

“This is going to sound incredibly blasé but I’m not worried about any of them,” he said. “I want them to come. Bring it on.”