This is the third part of an FT series analysing how the electric vehicle market is rapidly taking off

The Ford factory complex in Dearborn, Michigan has sprawled alongside the River Rouge for more than a century. It first made ships, then parts for Henry Ford’s wildly successful Model T and then began producing the T’s successor in 1928.

An industrial temple of an earlier age, Ford built the 2,000-acre site to vertically integrate his company’s operations. Raw materials flowed to the complex by freighter and railroad from an army of 6,000 suppliers.

The plant’s 4,200 employees currently make the F-150 pick-up truck, which for the last four decades has been the best-selling vehicle in the country.

FT Series: the EV revolution

Features in this series will include:

Part 1 Why the revolution is finally here

Part 2 How green is your EV?

Part 3 Will Americans ever buy electric vehicles?

Part 4 Batteries and China’s bid to dominate

Follow ‘electric vehicles’ using myFT to receive alerts when new stories are published

The Rouge, as locals call it, is now the launchpad for what Ford hopes will be a new era in American industrial history. The company has spent $950m to transform a parking lot into a new factory that will soon produce the first battery-powered version of the F-150 truck. America’s most iconic vehicle is going electric.

The automobile industry is on the verge of a fundamental transformation as demand for electric vehicles begins to pick up. Established automakers are being forced to plan for a future that does not include the combustion engines they have spent the last century developing.

Watching rivals in Europe and Asia prepare for this new era, America’s legacy car companies have also decided to stake their future on electric vehicles. Ford plans to invest $30bn in the development of EVs by 2025, while GM plans to invest $35bn over the same period.

The F-series trucks are the backbone of Ford’s business. In addition to the Dearborn facility, it plans to invest $11bn with South Korean battery maker SK Innovation to build plants in Tennessee and Kentucky to make electric versions of the F-150 and its larger cousins.

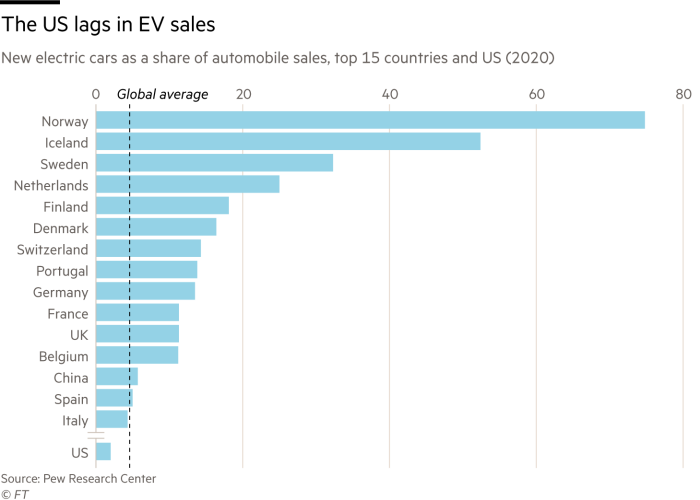

But one of the biggest questions for the industry is whether American drivers will embrace EVs in the same way that car buyers are starting to in China and parts of Europe. The US may be the home to Tesla, the most successful electric car brand and most highly valued automaker in the world, but it also has the most sceptical audience about EVs among any of the major auto markets.

Americans prefer bigger vehicles, drive longer distances and enjoy cheaper petrol than consumers in Asia or Europe — which could make electric vehicles a harder sell than in other countries. Climate issues have become a central part of the country’s political divisions, which could further limit their appeal.

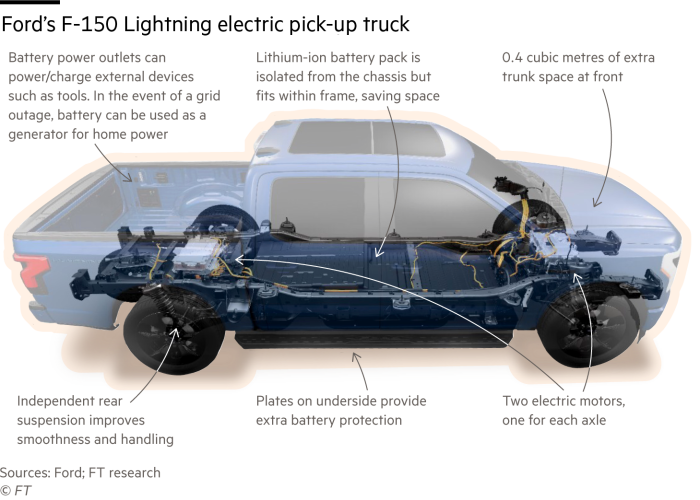

With the first models going on sale next year, the launch of the electric F-150 Lightning is therefore a pivotal moment for the industry. If Ford can convince many of the fans of its signature pick-up truck to go electric, then it will signal a deep change in the market.

“There is not a more important vehicle line in the history of the company than the F series,” says Tyson Jominy, vice-president of data and analytics at JD Power. “What they’re doing now is arguably taking the biggest risk they’ve ever taken with it, which is to get American consumers to buy an electric power-train.”

He adds: “This is the litmus test of will Americans go willingly toward electric vehicles.”

Gas guzzlers

The American car industry has been built in recent decades on the principle that bigger is better.

Automakers love pick-up trucks and sport utility vehicles. Bigger vehicles sell for higher prices, and in an industry with steep fixed costs, selling “cars by the pound” is more profitable than selling smaller vehicles.

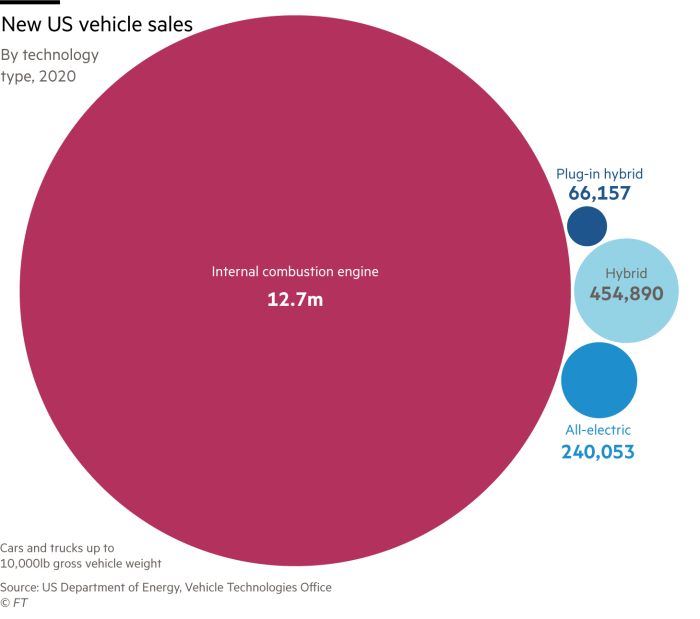

In the process, the companies have also been giving consumers what they want. Cars comprised only a quarter of the 14.4m US vehicle sales in 2020, with most American drivers opting for trucks, vans or SUVs. Ford sold 787,000 F-series trucks in 2020.

The American love affair with big vehicles is fuelled, literally, by petrol that costs less than elsewhere in the world. A litre of petrol cost 94 cents in the US the week of October 4, according to data provider GlobalPetrolPrices.com. That same litre cost $1.11 in Australia, $1.17 in China, $1.39 in India and $1.86 in France or the UK.

Adoption of electric vehicles has long lagged Europe, China and other parts of the world where governmental regulations helped to force an earlier rollout. EVs comprised 10 per cent of 2020’s new vehicle sales in Europe, 5.7 per cent in China, but only 2 per cent in the US, according to the International Energy Agency. Sales of electric or hybrid cars have actually slowed in the past few years.

Yet there are signs that American consumers have an open mind about electric cars. About 7 per cent of US adults said they currently have an electric or hybrid vehicle, according to Pew Research Center, while 39 per cent said they were at least somewhat likely to consider buying one the next time they shop for a vehicle. California last month announced plans last year to phase out gasoline-powered cars by 2035.

Lisa Drake, Ford’s chief operating officer for North America, said in September the company anticipated that a third of pick-up truck sales industry-wide will be fully electric by 2030. Ford says it has seen 150,000 reservations so far for the Lightning which starts at a $40,000 – a price that is competitive with rival trucks.

The fate of EVs in the US market will have a significant impact on the course of climate change over the next few decades. After China, the US is the leader in carbon emissions. And within the US, transportation is the biggest contributor — the sector generated 29 per cent of US greenhouse gas emissions in 2019, according to the EPA.

As a result, Joe Biden’s climate plans are focusing heavily on vehicles. In May, the president made an unscheduled stop in Michigan to test drive the Lightning. He tweeted later, “Get in folks, we’re going to win the competition for the 21st century.”

Three months later Biden signed an executive order calling for half of all new vehicles sold in the US to be electric by 2030. He was flanked by executives from Ford, GM and Stellantis — which comprises Fiat Chrysler and France’s PSA — who pledged that 40-50 per cent of their company’s sales would be zero-emission vehicles by that deadline.

Ford is not alone in eyeing the potential market for electric trucks. General Motors plans to sell the GMC Hummer and Chevrolet Silverado, a prime rival to the F-150. Electric start-up Rivian has started producing the R1T, and Tesla, which currently owns the US market for EVs, has unveiled a futuristic Cybertruck.

To win over wary drivers of pick-up trucks, the companies will need to overcome a number of questions. They will have to convince prospective customers that an electric vehicle has similar towing and off-road capacity as a truck with an internal combustion engine.

“You can’t tow half a trailer,” says IHS Markit analyst Stephanie Brinley. “The demands — there’s no compromise, and there’s scepticism about what battery electric vehicles can accomplish.”

The carmakers will also need to navigate the complicated politics around climate and cars in the US.

Tesla proved that electric vehicles can be cool, but it is a brand aesthetic that plays better in California than Oklahoma. For the Lightning to succeed, it must win over traditional truck buyers. At an event for the F-150 Lighting prototype, Debbie Dingell, a Democratic member of Congress from Michigan, proclaimed that the truck’s launch “made real for the world that electric vehicles aren’t a frou-frou California car. They are what real Americans drive.”

Electric vehicles are linked to environmentalism, often scorned by conservative politicians, and so far they have sold better in the politically liberal “blue states”, such as California and Hawaii. But trucks tend to sell better in the politically conservative states in the south and west.

That may be why Ford has chosen to heavily market the Lightning to commercial buyers — such as plumbing or contracting businesses. Petrol may be cheap in the US, but electricity is cheaper, driving down the truck’s total cost of ownership. Ford has a solid customer base among these groups and their typical patterns of usage — shorter journeys, vehicles parked in the same place at night — suit electric vehicles.

“Initially, there will be a political challenge with these vehicles,” says Jominy. “I don’t think Ford will play up the green angle. They will play up the dollar and cents angle, and the potential tech side . . . and to try to make it apolitical.”

Performance will be a critical selling point too. David Hunter, an owner of a petrol-powered F-150, has seen resistance among truck enthusiasts when they discuss the Lightning in online car forums. He says their scepticism reminds him of Ford’s introduction in 2011 of the EcoBoost, a fuel-efficient six-cylinder engine. At the time, some aficionados compared it unfavourably to the roaring V8, despite the smaller engine’s superior horsepower.

“Anytime there’s something new there’s going to be some pushback,” says Hunter, who works at an auto accessories company in South Florida.

Would he buy one? Hunter says he wants to drive it first. But the EcoBoost’s performance won converts, he says, and the Lightning could do the same. The engine may no longer roar at all, “but on the other hand, when your buddy bought the gas one and you blow his doors away, who really lost on that?”

Long-distance issue

For any potential buyer of electric vehicles, distance between charges is a critical issue. This is even more so in the US.

While the average US commute was 13 miles in 2017, Americans still travel long distances frequently enough that they require it in their personal transport, says Fitch Ratings analyst Stephen Brown.

Fitted with an extended range battery, which adds another $10,000 to the price, the F-150 Lightning can travel 300 miles. That distance, more than half the length of England, only takes a driver leaving Washington, DC, as far west as the Ohio border.

This shows that for the auto companies betting their future on EVs, their fate is not wholly their own. The pay-off on their investment, and whether consumers embrace the electrified parts of their line-ups, depends on the expansion of charging infrastructure in the US, which requires a combination of private investment and government funding.

There are more than 55,000 charging stations across the US, less than half the number of gas stations. Biden has said he wants to see 500,000 stations, but Congress only allocated $7.5bn to the project, half of what he proposed.

The charging stations that exist hardly offer a seamless user experience. They are operated by a cluster of competing companies with different business models and pricing. Some sell electricity, while others sell equipment and software. Volta’s model involves offering free power from charging stations covered in a large screen that displays ads to the driver.

Tesla charging stations use a plug shaped differently than the kind on other EVs.

The public is comfortable with petrol stations, Brinley says, while electric vehicle chargers are harder to access. Petrol stations “all have their regular gas price in three-foot letters”, while a charging station app might direct drivers to a site, just to leave them searching for the actual station.

“There’s a difference between finding it on the app and knowing which side of the building it’s on,” she says.

But Michael Farkas, chief executive of Florida-based Blink Charging, says that if consumers want to learn more about using charging infrastructure, those resources exist for them now. He sees the need for consumer education “as an opportunity” rather than a barrier to sales.

“With new technology, there’s a new learning curve,” he says. “Charging was the weakest link, but that’s not the case any more.”

The F-150 is “a game-changer” when it comes to EV adoption in the US, Farkas says, prompting him to buy Ford shares. But any shift in the balance between electric and petrol-powered vehicle ownership will necessarily happen slowly, because few people buy a new car every year. There are nearly 300m vehicles on the road, and the seasonally adjusted annual rate after September sales was forecast to be 12.3m.

“It’s going to take time, absent hard and fast rules,” Brinley says. “And the US isn’t good at hard and fast rules.”

As sales of the F-150 begin next year, the question will arise of how to tell whether Ford’s bet is paying off. Analysts say rising sales volume from the initial demand for 150,000 trucks over the next four or five years will signal success. If Ford begins offering more options to customise the truck, that, too, is a good sign. Alternatively, if the number of pre-orders goes from the current 150,000 “and then it drops off a cliff — that wouldn’t bode well”, Brown says.

Given its heavy investment plans, the company appears to be committed. “This is not a toe-in-the-water exercise,” Jominy says. “This is something they truly believe in and are working to make a success. If this works, then American can be switched over to electric vehicles. It’s an exciting play here. So, we’ll see.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here