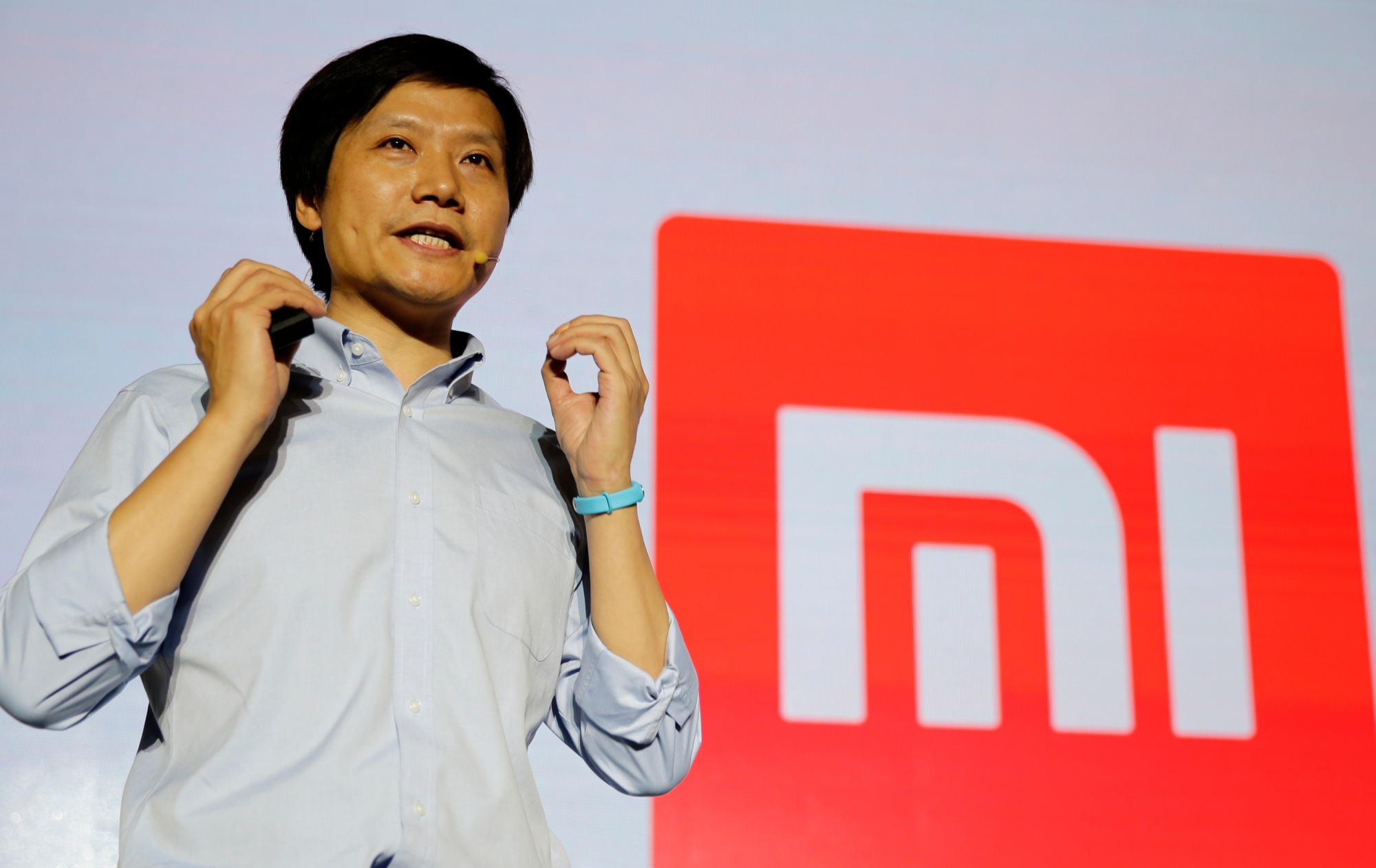

Lei Jun wants to take the Xiaomi brand on the road.

Xiaomi Corp.’s plans to move into electric vehicles are big, bold and brave. They’re also entirely in keeping with the smartphone company’s business model of developing a brand rather than the hardware it sells.

After announcing earlier this month that it will join the long list of those wanting to make cars, the Beijing-based company on Wednesday put a price tag on them: as low as 100,000 yuan ($15,000). According to the South China Morning Post, founder Lei Jun said that the first model will be either a sport utility vehicle or a sedan — ending any speculation that it could have been a sportscar or motorhome.

I’m stating the obvious when I predict that Xiaomi won’t be rolling any cars off its own production lines. In other words, it’s likely to embrace the looming business model of contract vehicle manufacturing — one that Tesla Inc.’s Elon Musk has dismissed. Yet pure outsourced smartphones were also a rarity when Lei Jun decided to turn that sector on its head.

At the time that Xiaomi entered the handset business a decade ago, it was such a pioneer that early contract partner Foxconn Technology Group didn’t quite take the company seriously. As an executive once told me, Foxconn’s sales team was unsure how to handle this unknown walk-in customer. When they found out it was headed by Lei Jun, they became eager to work with him. By training a computer scientist, he became famous for leading software maker Kingsoft Corp. and later heading up internet company UCWeb Inc. When he founded Xiaomi, the executive was a well-known angel investor and climbing up the ranks of China’s rich list.

Foxconn, meanwhile, was already making Apple Inc.’s iPhone through its Hon Hai Precision Industry Inc. unit. Its Hong Kong-listed mobile phone business, now called FIH Mobile Ltd., was stuck making devices for struggling brands like Nokia and Motorola.

Taking a gamble on Xiaomi wasn’t an obvious move for FIH at that time, but the advent of the Android operating system, cheaper phone chips, and commoditized touch screens — ditching the need for troublesome keyboards — paved the way for a fresh approach to the mobile phone business.

Xiaomi also gave up the traditional strategy of working with telecom operators and packing retail outlets with inventory. Instead, the company hung its shingle on the internet and shipped directly to consumers, allowing it to drastically cut costs and develop a more intimate relationship with buyers that fed back into development of future products. Mi Fandom got so big that some launch events attracted massive crowds and sold out products. And it wasn’t the only Chinese name around: Vivo, Oppo and OnePlus have all created loyal followings using a similar approach.

Xiaomi’s rise became legendary in the startup community. At one point, there was talk of a $100 billion valuation and the honor of being the world’s biggest unicorn. But hopes that the smartphone maker would become more like Facebook Inc., spinning its access to data into a treasure trove of ad and services revenue, met with more skeptical investors and it eventually listed in Hong Kong at half that value.

Along the way, the company started selling speakers, battery packs and even rice cookers. But one thing remained consistent — it outsourced almost everything. Although the company does have hardware engineers and works with vendors on specifications, that relationship is nowhere near as tight as Apple has with its suppliers. For some products, the Xiaomi connection is literally in name only — almost like a franchise-licensing model.

That’s why Lei Jun’s electric vehicle plans make complete sense. While incumbents are scrambling to build factories and set up supply chains, Xiaomi is likely to let everyone else do the work. By offloading the capital-intense side of hardware to those with the size and scale, cutting out the retail middle, and marketing direct to consumer, there’s every chance that the company can replicate its smartphone strategy by offering low-priced yet good quality alternatives to customers in emerging markets like China, India and Eastern Europe.

It also seems no coincidence that its decision to make a play for electric vehicles comes just as Foxconn starts its big push into the sector, complete with chassis and modularized car kits.

This is not to say that Foxconn will end up being Xiaomi’s manufacturing partner — other outsource carmakers already exist, including Magna International Inc. — but with a major contractor getting into the business, Lei Jun can be more confident than ever that there will be a robust catalog of companies willing to do the heavy lifting.

That leaves him doing what he does best, connecting with customers and building a brand.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net