On land that has yielded corn and beans, Jim Dane and some other Johnson County farmers may see something new produced.

Locally, the Dane name is associated with Dane’s Dairy, a popular ice cream shop just off Highway 1 now run by his sister. But Jim Dane still works 500 acres his family accumulated over the last century. Today, 200 acres are in the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program; some of the remaining 300 are in row crop.

But it’s not sweet corn, he’s producing. It’s fuel.

“I’m growing the crop for the most economic return I can get,” Dane said about his corn being turned in to ethanol.

For the past 20 years, as total corn production has fluctuated between 10 and 15 billion bushels, the 5 billion bushels used to produce ethanol nationwide has remained consistent, according to the USDA’s Economic Research Service.

The number of corn bushels grown in the United States has more than doubled since 1980. The majority of that growth came from corn raised for biofuel. But that demand for ethanol might have its limits.

David Swenson, an Iowa State University economist, told the Press-Citizen on Tuesday that without federal or state governments artificially inflating demand for ethanol, the product might be nearing its end. Even before the pandemic, increased fuel efficiency in cars, more Americans choosing not to own a motor vehicle, and the emergence of lower-cost electrical vehicles all translated, he said, to less gasoline consumed and less demand for additives like ethanol.

“From what I can tell, we may have reached peak motor fuel demand in the United States,” Swenson said. “One would expect no growth in the ethanol as a motor fuel. And the industry is worried.”

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST:

The Johnson County Solar Triangle project

A year ago, Dane was offered an alternative use for his land. Sean Kennedy of Megawatt Photovoltaic Development Inc., a utility-scale solar developer, approached him about a project that would continue generating energy but at a much larger scale.

Kennedy envisions a $4.7 million initial outlay for a project called the Johnson County Solar Triangle. It would require 1,500 acres, allowing for the photovoltaic infrastructure to provide up to 150 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 30,000 homes. By comparison, a recent MidAmerican Energy utility-scale solar project in Hills would generate two megawatts of electricity, or enough to power roughly 400 homes.

Kennedy believes the time is right for such a project, and Dane agreed.

“The cost of solar equipment has dropped to the point where … we can produce solar energy at a price competitive with other sources. Therefore, Iowa is skipping the build-out of small utility projects and moving right to the large-scale projects that can compete with a gas- or coal-fired power plant in generating capacity and cost of power,” Kennedy said.

Iowa is already a national leader in wind energy, and the Des Moines Register reported a dozen projects coming online that would add nine times more solar energy than the state currently produces. Two projects — Coggin Solar, Clēnera/Central Iowa Power Cooperative and Duane Arnold Solar, NextEra Energy Resources — will bring 790 megawatts of solar energy capacity to nearby Linn County. Kennedy was asked whether the size of his project would overshoot the demand for the energy, particularly given the number of large megawatt projects occurring across the state. He said that the 150 megawatts was an upper threshold and that the project would increase its capacity with demand.

“Five years ago, projects this large were only being built in locations with very strong solar resources and locations with good state incentives, such as the desert of California,” Kennedy said. “When we presented projects in Iowa that were 10 or 20 acres in size with a capacity of 1 to 2 megawatts, about the size of one wind turbine, people would always ask: ‘Will solar really work here?’ It seemed impossible. And it often was because energy prices were low and Iowa did not have state incentives to support utility-scale solar.”

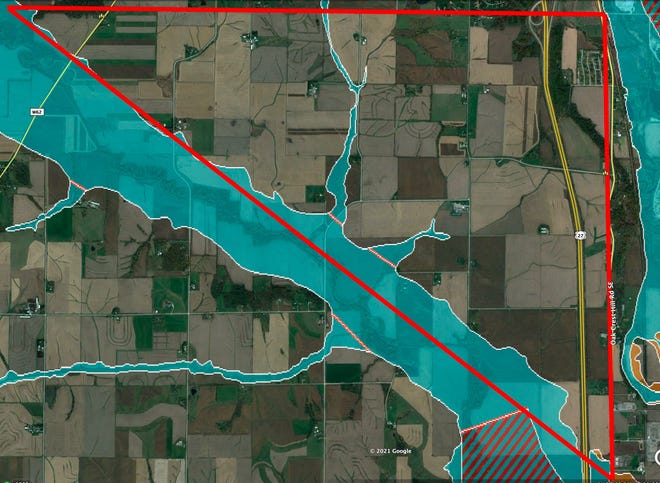

The Triangle would consist of agricultural land south of Osage Street SW and between the Iowa River floodplain and the Old Man’s Creek floodplain. There is 4,000 acres there, and Kennedy is trying to sign farmers up.

Dane was an early landowner to jump on board. He said it was comforting to know Kennedy’s plan was to continue to produce energy. Once the contract is complete and the lease is up — after the lifecycle of the solar energy equipment — the ground could return to row crop if he wanted.

Kennedy said he’s reached 1,100 acres of dedicated land and is recruiting more farmers. But he’s approaching a deadline. By July 22, he must submit an application to the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, which provides high-voltage electrical transmission service to the Midwest, parts of the South and even into Canada.

Landowners turn to row crops as a means of generating income. Swenson said, if a rent agreement is lucrative enough, some landowners in the Johnson County triangle may ditch their crops and turn to solar energy. The savings on labor might be worth a trade. It was for Dane.

“My thought is everybody is in a different situation, and you need to be comfortable that this will work for you. If you have acres that are ready to farm and you’re looking to do something productive in ag for the next decades, maybe you don’t want to put your land into solar,” Dane said. “But I don’t have the acres I’m eager to farm at this time.”

Zachary Oren Smith writes about government, growth and development for the Iowa City Press-Citizen. Reach him at zsmith@press-citizen.com, at 319 -339-7354 or on Twitter via @ZacharyOS.