Vistra Corp.

owns 36 natural-gas power plants, one of America’s largest fleets. It doesn’t plan to buy or build any more.

Instead, Vistra intends to invest more than $1 billion in solar farms and battery storage units in Texas and California as it tries to transform its business to survive in an electricity industry being reshaped by new technology.

“I’m hellbent on not becoming the next

” said Vistra Chief Executive

Curt Morgan.

“I’m not going to sit back and watch this legacy business dwindle and not participate.”

A decade ago, natural gas displaced coal as America’s top electric-power source, as fracking unlocked cheap quantities of the fuel. Now, in quick succession, natural gas finds itself threatened with the same kind of disruption, only this time from cost-effective batteries charged with wind and solar energy.

Natural-gas-fired electricity represented 38% of U.S. generation in 2019, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA, and it supplies round-the-clock electricity as well as bursts during peak demand. Wind and solar generators have gained substantial market share, and as battery costs fall, batteries paired with that green power are beginning to step into those roles by storing inexpensive green energy and discharging it after the sun falls or the wind dies.

Battery storage remains less than 1% of America’s electricity market and so far draws power principally from solar generators, whose output is fairly predictable and easier to augment with storage. But the combination of batteries and renewable energy is threatening to upend billions of dollars in natural-gas investments, raising concerns about whether power plants built in the past 10 years—financed with the expectation that they would run for decades—will become “stranded assets,” facilities that retire before they pay for themselves.

Across the country, much of the growth in renewable energy to date has been driven by state mandates that have required utilities to procure certain amounts of green power, and by federal tax incentives that have made wind and solar more economically competitive.

But renewables have become increasingly cost-competitive without subsidies in recent years, spurring more companies to voluntarily cut carbon emissions by investing in wind and solar power at the expense of that generated from fossil fuels. And the specter of more state and federal regulations to address climate change is accelerating the trend.

President Biden is proposing to extend renewable-energy tax credits to stand-alone battery projects—installations that aren’t part of a generating facility—as part of his $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan, which could add fuel to an already booming market for energy storage.

Still, as batteries help wind and solar displace traditional power sources, some investors view the projects with caution, noting that they, too, could become victims of disruption in coming years, if still-other technological advances yield better ways to store energy.

And while batteries can provide stored power when other sources are down, most current batteries can deliver power only for several hours before needing to recharge. That makes them nearly useless during extended outages.

Gas vs. green

Gas-fired power plants are already struggling to compete with wind and solar farms.

Duke Energy Corp.

, a utility company based in Charlotte, N.C., that supplies electricity and natural gas in parts of seven states, is still looking to build additional gas-fired power plants. But it has started to rethink its financial calculus to reflect that the plants might need to pay for themselves sooner, because they might not be able to operate for as long.

Duke has proposed building as much as 9,600 megawatts of new gas-fired capacity in the Carolinas to help meet demand as it retires coal plants and invests more heavily in solar and wind power. But in regulatory filings, the company has acknowledged that any new gas plants could become stranded assets, failing to pay for themselves as technology advances. A megawatt of electricity can power about 200 American homes.

Share Your Thoughts

Do you think money will begin to flow more rapidly into green energy? Join the conversation below.

To remedy that, Duke in public filings said it is considering shortening the plants’ expected lifespan from about 40 years to 25 years and recouping costs using accelerated depreciation, an accounting measure that would let the company write off more expenses earlier in the plants’ lives. It may also consider eventually converting the plants to run on hydrogen, which doesn’t result in carbon emissions when burned.

“This is one risk that we’re looking at, but we need to look at that risk across every technology decision we make,” said Glen Snider, Duke’s director of integrated resource planning, noting that all power investments face potential disruption.

More than 60,000 megawatts of gas-fired capacity came online in the U.S. since 2014, according to the EIA. Like coal plants, many of which have been forced to close early, gas plants were financed with the expectation that they would operate for decades.

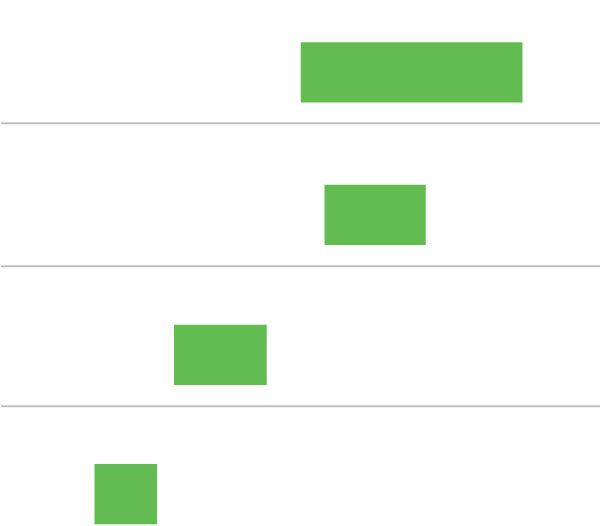

Going Green

Batteries are becoming cost-competitive with gas-fired power plants.

Cost range of generating or discharging power in the U.S., by source

Solar photovoltaic + storage†

Stranded costs resulting from coal retirements are typically modest because many of the plants were built decades ago and nearing the end of their useful lives, according to

Much of the nation’s gas fleet, on the other hand, is relatively young, increasing the potential for stranded costs if widespread closures occur within the next two decades.

Gas plants that supply power throughout the day face the biggest risk of displacement. Such “baseload” plants typically need to run at 60% to 80% capacity to be economically viable, making them vulnerable as batteries help fill gaps in power supplied by solar and wind farms.

Today, such plants average 60% capacity in the U.S., according to

a data and analytics firm. By the end of the decade, the firm expects that average to fall to 50%, raising the prospect of bankruptcy and restructuring for the lowest performers.

“They are under threat from tons of renewables,” said Sam Huntington, IHS Markit’s associate director for gas, power and energy futures. “It’s just coal repeating itself.”

It took only a few years for inexpensive fracked gas to begin displacing coal used in power generation. Between 2011, shortly after the start of the fracking boom, and 2020, more than 100 coal plants with 95,000 megawatts of capacity were closed or converted to run on gas, according to the EIA. An additional 25,000 megawatts are slated to close by 2025.

Grid-scale batteries

Most grid-scale batteries are made of lithium ion, the same sort of technology that powers electric vehicles. They look similar to large shipping containers and are often grouped together to create arrays capable of providing large amounts of power. Some are attached to renewable energy sources, while others stand alone and draw power from the grid.

Batteries are most often paired with solar farms, rather than wind farms, because of their power’s predictability and because it is easier to secure federal tax credits for that pairing. Some companies are developing wind farms paired with batteries, and the market is expected to grow as technology costs fall.

Already, the cost of discharging a 100-megawatt battery with a two-hour power supply is roughly on par with the cost of generating electricity from the special power plants that operate during peak hours. Such batteries can discharge for as little as $140 a megawatt-hour, while the lowest-cost “peaker” plants—which fire up on demand when supplies are scarce—generate at $151 a megawatt-hour, according to investment bank

Vistra’s Moss Landing plant houses over 4,500 racks of batteries in a retired natural-gas plant.

Solar farms paired with batteries, meanwhile, are becoming competitive with gas plants that run all the time. Those types of projects can produce power for as little as $81 a megawatt-hour, according to Lazard, while the priciest of gas plants average $73 a megawatt-hour. Major battery projects under way in New York and California are driven in part by state mandates to slash carbon emissions, not just improving battery economics.

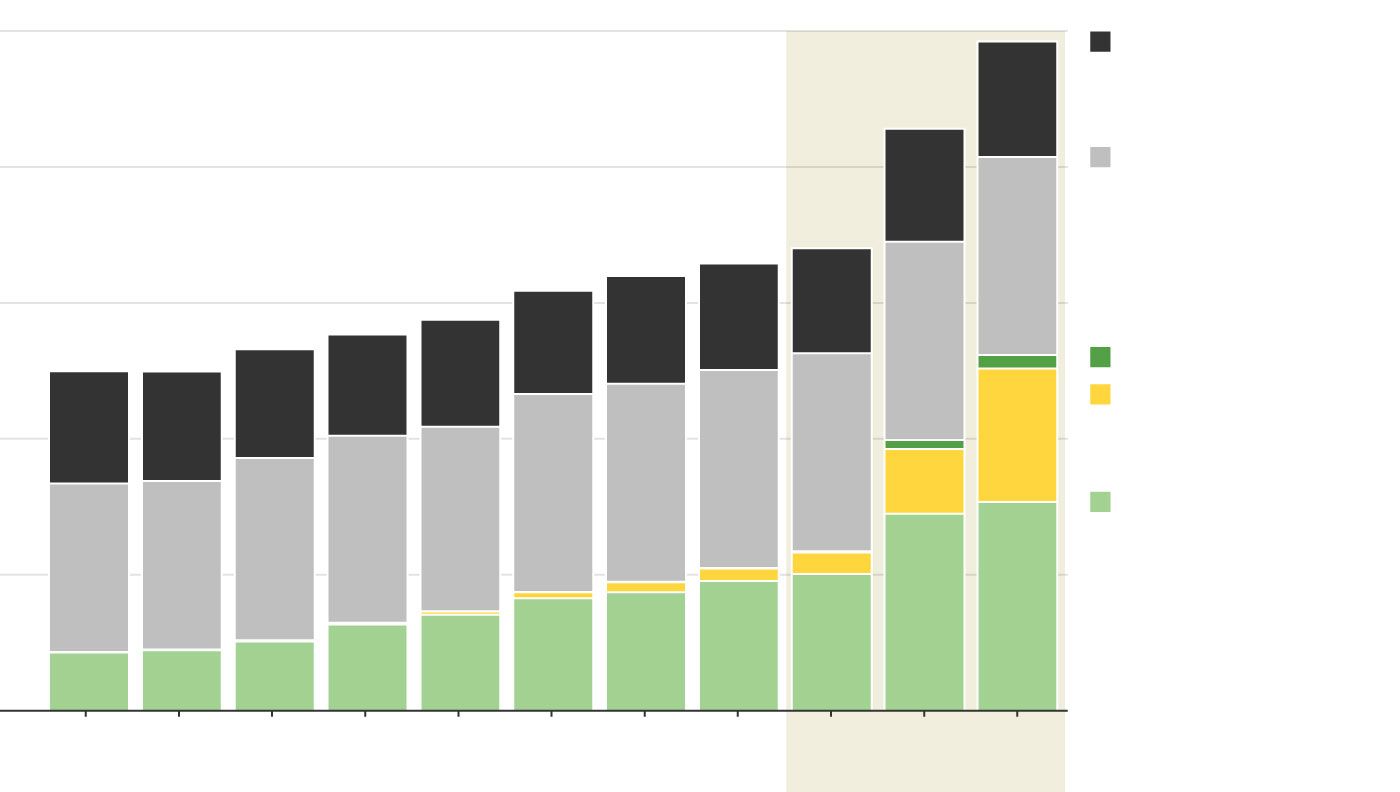

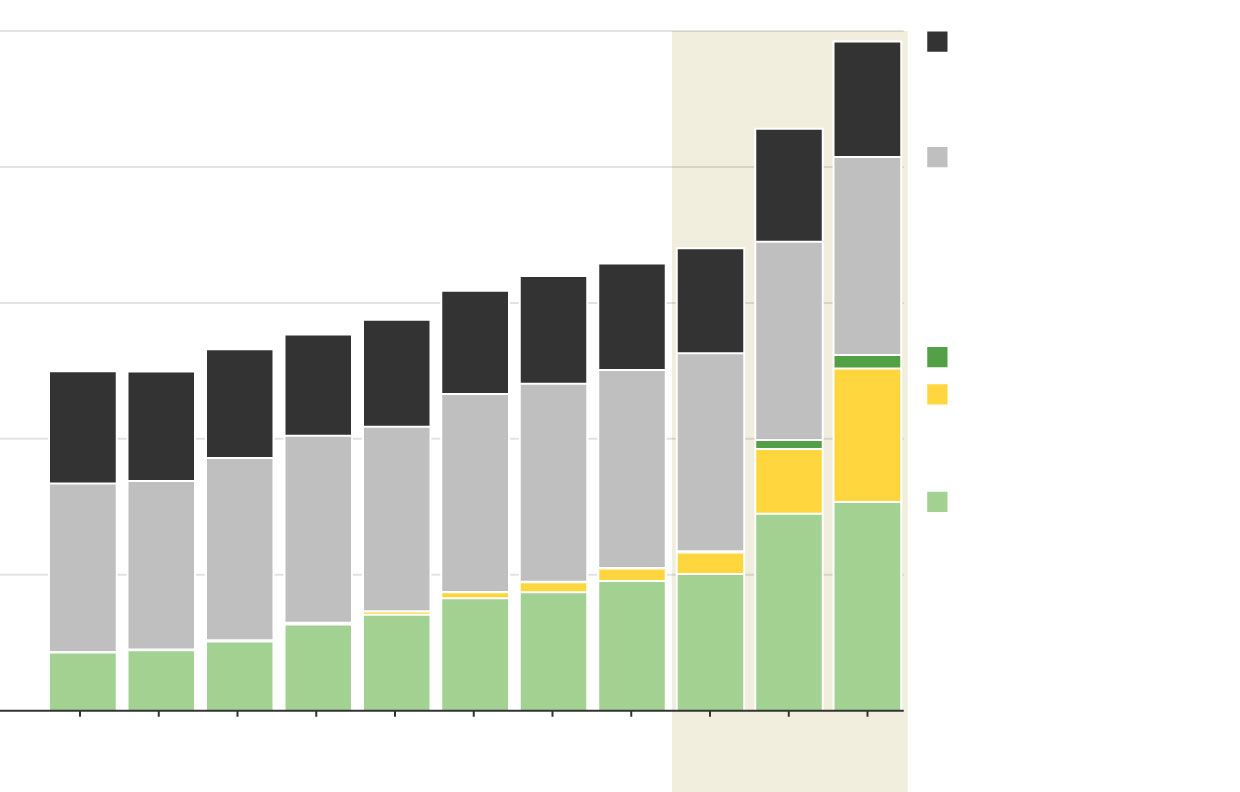

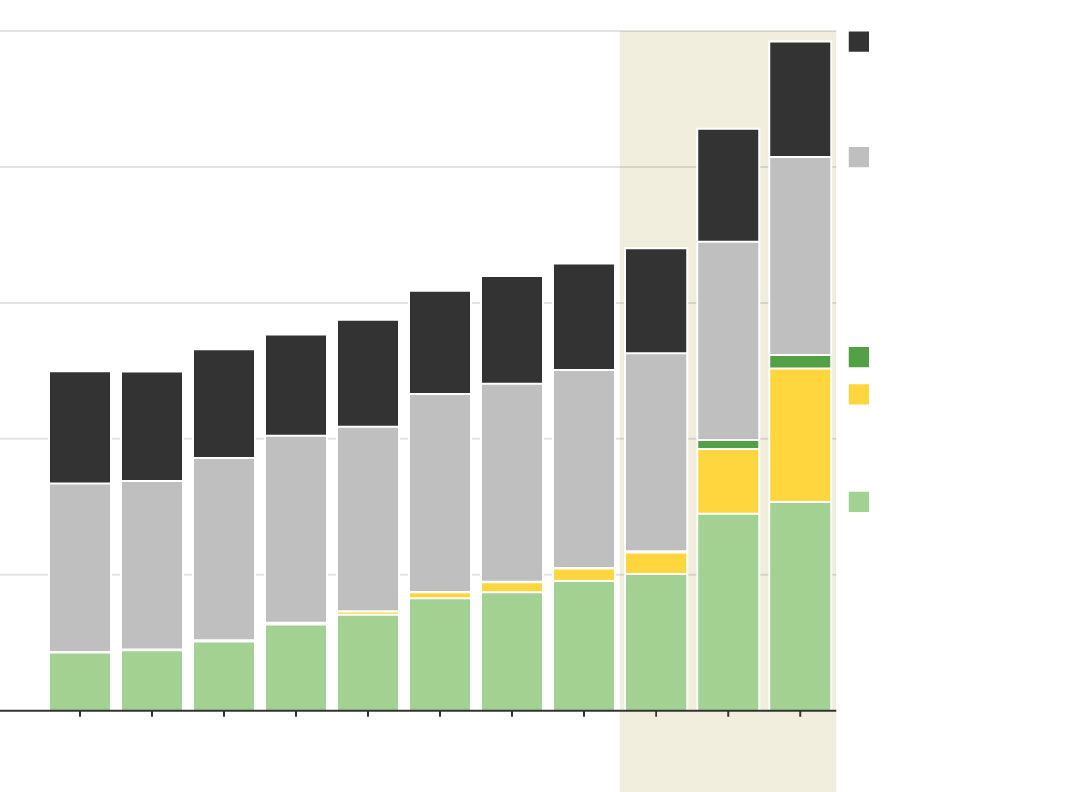

Even in Texas, a state with a fiercely competitive power market and no emissions mandates, scarcely any gas plants are under construction, while solar farms and batteries are growing fast. Companies are considering nearly 88,900 megawatts of solar, 23,860 megawatts of wind and 30,300 megawatts of battery storage capacity in the state, according to the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, which operates its regional power grid. By comparison, only 7,900 megawatts of new gas-fired capacity is under consideration.

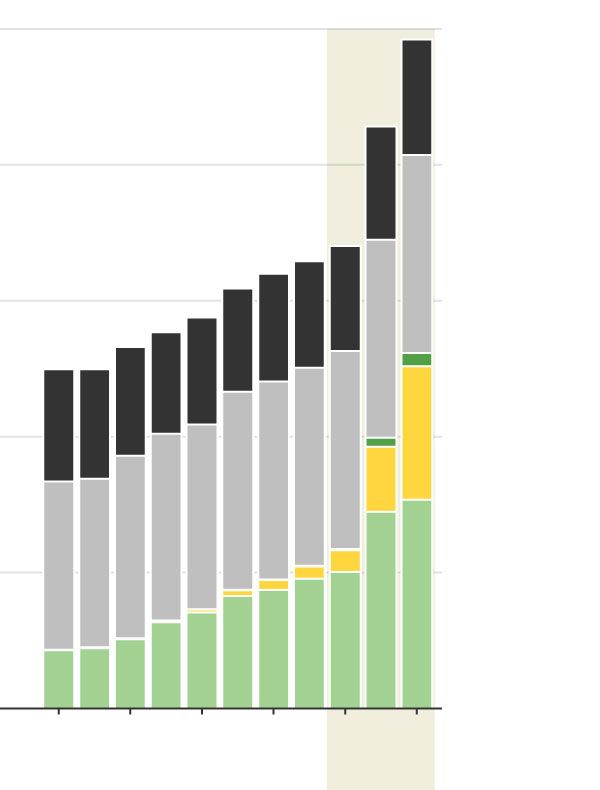

Texas Power Generation

Wind, solar and battery installations are growing quickly in Texas, while natural-gas capacity has remained flat.

Power companies and grid regulators must consider the prospect that the new sources may not be as reliable as power plants they replace, at least initially, and the Texas blackouts in February illustrated that concern.

The state experienced days of devastating power outages as a powerful winter storm froze many of the state’s sources of power, including wind turbines, gas and nuclear power plants, just as demand was spiking due to freezing temperatures.

Even if Texas had more battery storage, executives and analysts say, it likely wouldn’t have done much to ease the multiday supply crunch, which occurred during a season when wind and solar farms aren’t as productive. Most current storage batteries can discharge for four hours at most before needing to recharge.

California last summer experienced the consequences of quickly reducing its reliance on gas plants. In August, during an intense heat wave that swept the West, the California grid operator resorted to rolling blackouts to ease a supply crunch when demand skyrocketed. In a postmortem published jointly with the California Public Utilities Commission and the California Energy Commission, the operator identified the rapid shift to solar and wind power as one of several contributing factors.

Displaced

Like many power companies, Vistra doesn’t expect gas plants to be immediately displaced. Mr. Morgan, who has closed a number of Vistra’s coal-fired and gas-fired plants since becoming CEO in 2016, said he anticipates most of the company’s remaining gas plants to operate for the next 20 years.

Once complete, the batteries at Moss Landing will supply 400 megawatts of power for four hours.

After 2030, he expects they’ll be used far less frequently as batteries augment the electricity supplied by wind and solar farms. Vistra is developing what is expected to be the world’s largest power-storage project at Moss Landing, just north of Monterey, Calif. The batteries are situated where turbines once sat inside a retired natural-gas plant spanning the length of nearly three football fields. Once complete, the batteries will supply 400 megawatts of power for four hours, enough for more than 225,000 homes.

Enormous batteries are also edging out older gas plants elsewhere across the country. Florida Power & Light Co., a utility owned by

NextEra Energy Inc.,

began construction earlier this year on what is expected to be the world’s largest solar-powered battery system, which will replace two natural-gas turbines at a neighboring plant. The Manatee Energy Storage Center will have 409 megawatts of capacity, enough to power Disney World for about seven hours.

In Texas, the birthplace of the modern fracking industry, companies for years have used the bounty of the boom to fuel natural-gas peaker plants, which could earn large sums in the state’s wholesale power market when demand spiked.

Some are now having second thoughts after a massive build-out of wind and solar farms has made it more difficult for gas plants to compete, and batteries threaten more disruption.

Quantum Energy Partners, a Houston-based private-equity firm, in the last several years sold a portfolio of six gas plants in Texas and three other states upon seeing just how competitive renewable energy was becoming. It is now working to develop more than 8,000 megawatts of wind, solar and battery projects in 10 states.

“We pivoted,” said Sean O’Donnell, a partner in the firm who helps oversee the firm’s power investments. “Everything that we had on the conventional power side, we decided to sell, given our outlook of increasing competition and diminishing returns.”

Transmission lines carry power from Moss Landing to surrounding areas.

Write to Katherine Blunt at Katherine.Blunt@wsj.com

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8