Two 200m (656ft) chimney stacks and a boiler house were demolished at Ferrybridge Coal Power Station in West Yorkshire in August 2021.

Two 200m (656ft) chimney stacks and a boiler house were demolished at Ferrybridge Coal Power Station in West Yorkshire in August 2021.

Image: David Autumns / Alamy Stock PhotoIncongruous on the worn stone of a heritage-listed church in Camden, London, solar panels flash, attempt discretion under diffused English sunlight. Nearby, long black sheets catch the sun atop a National Health Practice’s modern brick and glass structure.

Despite high solar energy potential, and incentives from the Maharashtra State Government and power companies for its use and buy-back, renewables currently account for just 5 percent, barely denting the predominance of coal. MCAP does not specify any particular action to phase out coal.

“No mission can be successful without people’s participation.” the self-reliant India policy headlined. People, including environmentalists, youth groups, tribal dwellers and politicians across party lines all participated to protest against coal extraction from forests.

Maharashtra Environment Minister Thackeray opposed the Centre’s plan to mine in the vicinity of the Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra. When the project was dropped, he tweeted, “This is welcome news.”

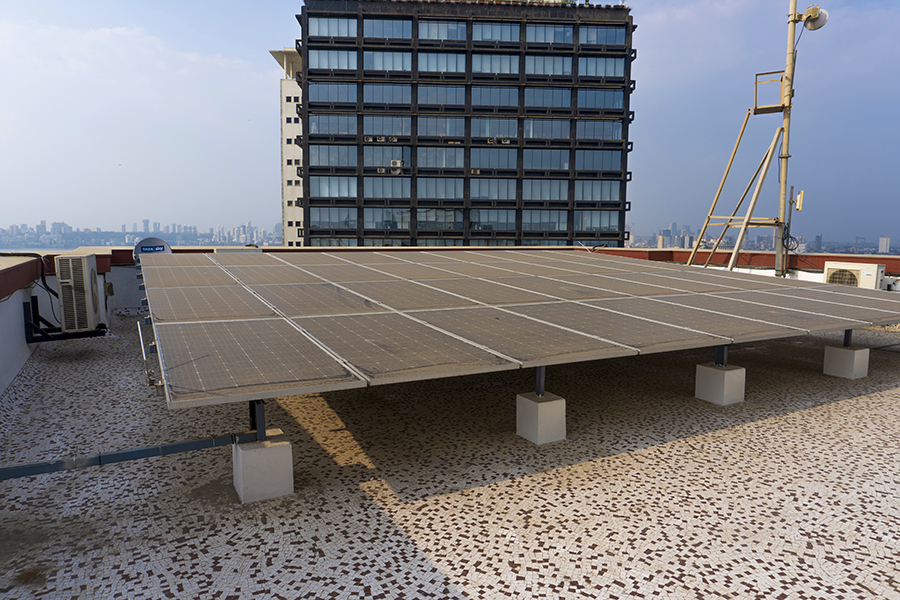

Solar cell panels for solar energy are being installed on the terrace of an office building near Marine Drive in Mumbai

Image: Shutterstock

In their concern for the future of our earth and life as we know it, individuals and community groups not only align with CoP26 goals, augment the grid and provide clean energy locally, but they also create awareness, give people a sense of control and motivate others in their circles to do the same.

Like India, the UK is also experimenting with diverse models of solar and other clean energy production and delivery including institutional, participatory and community models.

Two years before Mumbai’s MCAP, alongside 27 of 33 London boroughs, Islington and Camden Councils declared a state of climate emergency in 2019. To deliver on their commitment to build clean, affordable energy systems that leave none of their residents behind, partnerships with community groups, including PUNL, add much-needed momentum.

The thrust of most institutional and community renewable models is to meet the requirements of fixed infrastructure. However, demanding immediate attention from governments and communities is transport, another crucial sector with its own steeply escalating need for power, all set to overtake the pre-existing demands of fixed infrastructure.

EVs align with another important goal of CoP26, to “speed up the switch to electric vehicles”. India’s national policies aim to replace 30 percent of vehicles with EVs by 2030, and MCAP names EVs as key for greenhouse gas reduction.

Sara de la Serna, who worked for Element Energy, UK, explains that barriers to EVs include cost and charging infrastructure. “The switch from traditional fossil fuel driven vehicles to EVs requires significant market, consumer perception, infrastructure and behavioural changes to be successful,” she says.

Like the UK, EV manufacture in India will also face daunting challenges, and require significant behavioural change and financial investment in infrastructure and manufacturing technologies, including EV-friendly road design, power outlets and incentives to car manufacturers. Together, these represent a significant share of India’s Budget.

Side-by-side investments in EVs and solar power will demonstrate India’s success or failure in achieving their stated aim of lower emissions alongside widespread EV use.

For most countries, action to meet the decision of CoP24 held in 2018 and annexed to the Agenda of CoP26 “to avert, minimize and address loss and damage and reduce disaster risks” is led by time-bound replacement of coal.

“It’s time for countries around the world to set out clear plans to consign coal power to the history books,” says Alok Sharma, surrounded by thick smoke as he watches the two chimneys in Yorkshire crumble and disintegrate, the trigger still in his hand.

The solar panels on the old Camden church shine bright. They highlight people’s aspirations away from the climate emergency initiated by coal. Across the UK, over 400 community energy groups deliver rooftop solar, LED lighting and retrofit solutions for community and residential buildings. In India, individuals and communities innovate new systems to deliver solar power.

MCAP addresses action points in all major sectors but it headlines the power sector, with 71 percent contribution, as most responsible for greenhouse gas emissions. It emphasises that Mumbai faces direct impacts of sea-level rise and would be underwater by 2050 without immediate and effective action. With the rest of India and the rest of the world, Maharashtra is already experiencing increasingly devastating climate events like droughts, cyclones and floods.

Inexplicably under the circumstances, Mumbai, which uses 2300MW, nearly half of Maharashtra’s power already, is escalating investments and infrastructure designed to increase private vehicles rather than investing in public transport. These investments will increase greenhouse gases from traditional vehicles and the EVs which are projected to replace them.

The World Habitat Day theme, with its theme ‘Accelerating urban action for a carbon-free world’ to “amplify the global Race to Zero Campaign”, encourages “local governments to develop actionable zero-carbon plans in the run up to the international climate change summit COP26 in November”.

Ahead of CoP26 and the Climate Week NYC 2021 Maharashtra Environment Minister Aaditya Thackeray reiterated his own stand, “We do not have the luxury of time. Maharashtra will set an example of how subnational governments can act on climate change despite being a massively industrialised state.”

Crossing the Thane Creek Bridge into Mumbai, tapered pylons reach for the sky, inter-connected to each other and to the city of Mumbai in vibrant lines alive with current. The power they supply is Mumbai’s life-blood, whose cleanliness Mumbai depends on absolutely for its health and wellbeing.

Mumbai’s uses half of Maharashtra’s power, and Maharashtra is India’s highest power consumer. By 2030, India will overtake the EU to become the world’s third largest power consumer.

The earth and all its inhabitants face existential threat, a climate emergency, not merely a climate inconvenience. As the fourth-largest greenhouse-gas emitter in the world already, India has potential to make or break the CoP26 aspiration of 1.5 degrees.

(Sumaira Abdulali is the convenor of Awaaz Foundation, Mumbai. Tanuja Pandit is the director of Power Up North London)