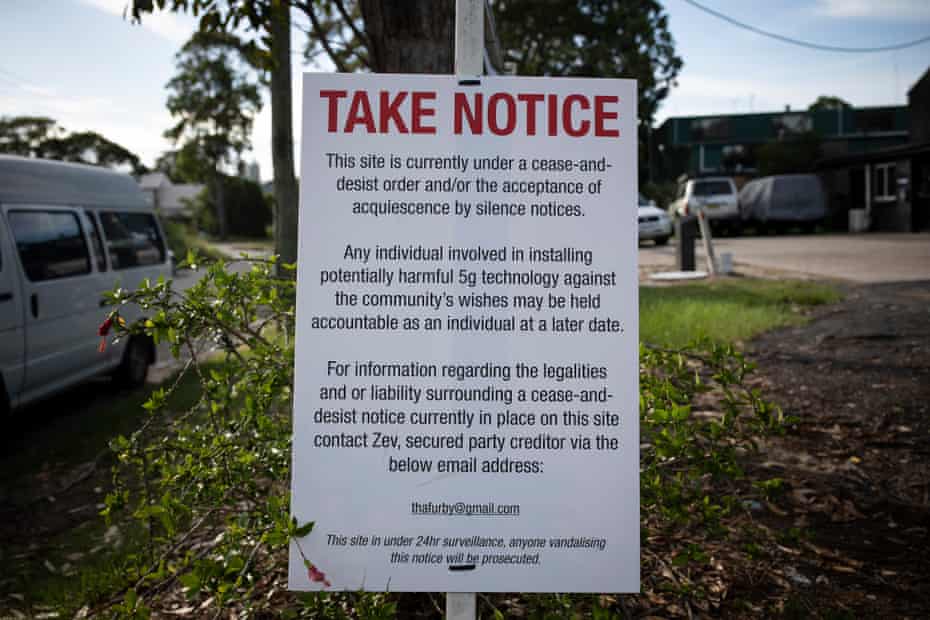

When Michael Marom steers his Telstra-branded company car past the site of a planned 5G tower on the streets of Mullumbimby, it draws a now predictable response.

Someone is watching, always, and news of his presence quickly ripples through the faithful.

“They call themselves the protectors of the tower,” Marom says.

“They have someone there all the time, so what happens is that as soon as you drive past in a Telstra vehicle, within about 15 minutes there’ll be four or five other cars there.”

Among the protectors will most likely be those who, despite all evidence to the contrary, believe 5G’s electromagnetic energy is harming babies, or interfering with bee populations, insects and birds, which are suddenly falling out of the sky.

The more extreme might believe 5G is spreading Covid-19, or that face masks have been equipped with 5G antennas.

There’s no aggression. No abuse.

But a lesson lies in the sheer speed of the response.

These are the diehards. They are well connected and organised. Fervent in their belief of the evils of 5G and ready to act on it with little notice.

Marom has come to learn that these minds aren’t for changing. The battle lies elsewhere.

“The job that we see in front of us is to make sure that people who do want information, and are rational about receiving that information, that they’re communicated to effectively,” he says.

Marom has amassed a surprising level of expertise in countering misinformation. His view is shared by every expert who spoke with the Guardian about strategies to counter conspiratorial thinking and disinformation.

It was never in the job description, he jokes.

But he, and Telstra more broadly, have found themselves devoting significant time and energy to tackling misinformation and conspiracy head-on.

Last year, Telstra deployed a specific communications campaign through advertisements and social media content, blending a mixture of levity and fact, using comedian Mark Humphries as its spokesperson.

The aim, much like Marom’s, was to target the fence-sitters, those who are unsure about the facts, not those who are hardened in their conspiratorial thinking.

The fact that Telstra needed to mount such a campaign, though, raises a question.

In an age of eroding trust, entrenched institutional scepticism and uninhibited social media amplification of untruths, should we be leaving this fight to workers like Marom and companies like Telstra?

Or does the federal government need to step into the ring? And how does it do so effectively?

When should government get involved?

In early 2020, as Covid-19 took hold, the world was ripe for conspiracy. Anti-5G theories began to flourish.

In the UK, groups convinced of a link between 5G and the spread of the virus set fire to dozens of telecommunications towers in April. The mayor of Liverpool, Joe Anderson, also received threats over the theory, and cabinet secretary Michael Gove described it as “dangerous nonsense”.

In early May, rallies took place on streets of most major Australian cities, including in Melbourne, where protesters sought to link the Cedar Meats Covid-19 outbreak to a nearby telephone tower.

Prof Axel Bruns, an expert with the Queensland University of Technology’s digital research media centre, says the Australian government’s response was flawed.

It put out a five-paragraph statement in mid-May, disputing the link between Covid-19 and 5G, accompanied by a YouTube explainer on electromagnetic energy. That video has so far failed to attract even 2,500 views.

Similar media releases were issued by the communications minister, Paul Fletcher, and then-chief medical officer Brendan Murphy.

The response came an entire month after the UK arson attacks and a week after Australia’s nationwide protests. It was far too late to stop the conspiracy taking hold, Bruns says.

“Of course I’m saying this with the benefit of hindsight, and there will have been at least some ad hoc statements in press conferences and from tech companies before the official releases, but these late responses enabled the conspiracy theory to circulate for weeks without definitive official comment.”

United States Studies Centre research associate Elliott Brennan, who is studying government responses to conspiratorial thinking, says Australia is not alone in misjudging its response.

Governments, he says, must transition from viewing the issue as trivial, or a silly import from the US, to “a fundamental threat to the social fabric of the country”.

“There doesn’t appear to be a government in the world that has not underestimated the threat these conspiracy theories pose,” Brennan says. “Unfortunately, this attitude has allowed their reach to creep into elections and within the institutional halls of government. That has been very clear in the United States and Australia.”

So when is the right time for government to act?

Wading in too early risks attracting unwanted attention to a conspiracy and, perversely, giving it a legitimacy it might not otherwise enjoy.

Responding too late can allow the fence-sitters, the ordinary citizens, to be exposed to misinformation and dragged into the conspiracy quagmire.

“So the challenge – and it’s a significant one – is to hit that spot where you can deter the wider spread of conspiracist claims by making it clear to ordinary people that there’s no merit to the claims, and that spreading them would cause harm to others,” Bruns says.

“There may be a need here to invest in more media monitoring – social and mainstream – in order to detect emerging misinformation and formulate responses early so they’re ready to be rolled out when the time comes.”

It’s not the only challenge.

Who can be won over and how?

Governments, it can be safely assumed, are bereft of trust among those perpetuating conspiracies.

Experts broadly agree that it is near pointless trying to convince the diehards.

Bruns says the aim instead must be to protect ordinary citizens from exposure and stop them sharing misinformation.

Others say the government’s target should be trusted figures who have a relationship with those engaging in conspiratorial thought: friends and family, or doctors, for example.

“This is where government-funded advertising and education campaigns, despite the inherent scepticism of conspiracy theorists themselves, could be most valuable,” Brennan says. “Armed with the right information, those who share strong social bonds with an affected individual are the most likely to get through to them.”

Even then, such an approach is reactive only.

It does nothing to get to the root cause of the problem: the societal conditions that allow conspiracy to fester.

University of Technology Sydney lecturer Francesco Bailo, an expert on the use of digital and social media in politics, is working with colleagues Amelia Johns and Marian-Andrei Rizoiu on strategies to protect online communities from disinformation.

Bailo says conspiratorial thinking is fundamentally a trust problem. But distrust is complex and varying.

The cause of distrust differs greatly from person to person, a result of their individual experiences and belief systems, and may be outwardly directed at different institutions or individuals.

“In line with what [has been] found elsewhere, we are beginning to notice that even if online communities do emerge around a shared sense of distrust … alternative narratives can still attract different people, that is, people who possibly have different justification for their lack of trust,” he says.

The point of this, Bailo says, is that any government intervention must be designed to address the specific trust issues of the target audience.

In the US, Black Americans may oppose vaccination for a range of complex reasons, including personal experiences with public authorities and a history of institutional racism.

“And yet this can clearly not explain why wealthy, white Californian parents might have developed very strong opinions against the same vaccine,” Bailo says.

Bailo sees value in government intervention, saying it can find “a receptive audience in the people located on the most moderate side of that spectrum”.

“And there is also a very significant value in framing the message based on the specifics of the target audience,” he says. “So, what does motivate their lack of trust? And who – what kind of public personality – can help strengthen their trust or reduce their distrust?”

There are other roles for government, too.

Regulation of social media companies – which have effectively incentivised conspiracies – is a clear and obvious policy lever, Brennan says.

A broader prevention campaign, promoting e-safety education for adults, rather than just through primary and secondary education, would also be beneficial.

Striking the right tone

The fight, as Bruns sees it, is asymmetrical. The two sides are fighting on different battlegrounds.

Government, serious media, and experts are speaking to one specific audience.

Influencers, gullible celebrities, conspiracy theorists, populist politicians, and the tabloid and entertainment media that report on them, are speaking to another.

Bruns believes government needs to insert itself directly into the spaces where the conspiracist claims are circulating unchecked among mainstream audiences.

“This doesn’t mean getting into hardcore conspiracist groups – they’re too far gone to be reached by factchecks and similar content – but it’s critically important to ensure that tabloid, celebrity, entertainment, sports, and related media cover the correct information as much as they cover celebrities and influencers spouting mis- and disinformation, because that’s where ordinary, non-conspiracist people are most likely to encounter these conspiracy theories,” he says.

That might mean, for example, government enlisting celebrities or influencers to create humorous and shareable content such as memes.

There might be a tendency by governments to view such an approach as beneath them. But Bruns says that just “cedes the field to the other side”.

Telstra’s campaign is illustrative here. It attempted precisely the kind of approach Bruns speaks of, using short clips featuring a respected celebrity, which blended humour and direct, factual messaging that addressed common myths about 5G.

The content was easily shareable and is understood to have reached millions.

On the ground, Marom says his approach is never to ignore or laugh off concerns about 5G. Instead, he attempts to build community support and understanding – simply by talking with those who are willing to listen.

“Everybody’s entitled to an opinion, but what we do want to do is rationally and calmly say ‘these are the facts’.”

From anti-vaxxers to 5G conspiracists, the Web of lies series explores the growth and spread of misinformation and conspiracy thinking in Australia.