At the southernmost tip of Texas, alongside the Gulf of Mexico, a gleaming stainless steel rocket has been rising from the salt marshes.

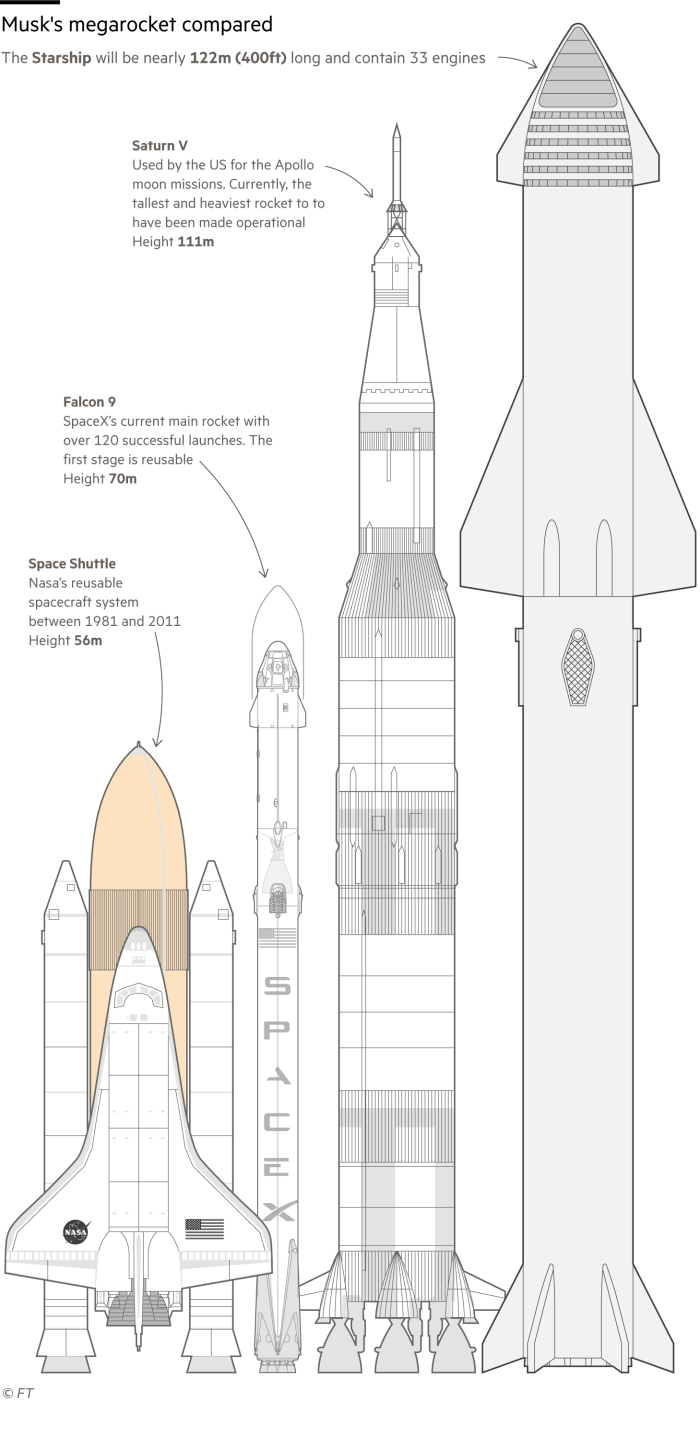

At nearly 400ft, the new SpaceX rocket will eventually be taller than the Saturn V that carried Nasa’s Apollo missions to the moon, and its 33 engines will deliver twice the thrust. For Elon Musk, SpaceX’s founder, it is meant to play a key role in one day establishing a human colony on Mars.

But the rocket, dubbed the Starship, could have a far more immediate impact on a space industry that has already been shaken by Musk’s ambitions. With the power to carry as much as 100 tons into low orbit around the Earth, his admirers claim Musk is about to transform the economics of the launch business.

“It’s game over for the existing launch companies,” says Peter Diamandis, a US space entrepreneur. “There’s no vehicle out there on the drawing board that could compete.”

Musk’s space company still has some way to go to live up to the promise, including winning regulatory clearance to launch Starship from its Texas site and showing that it can reliably reach space while returning both the rocket’s stages for reuse — an essential step in reducing launch costs.

Also, many experts question whether a large rocket designed to colonise another planet can double up as an all-purpose transport for more varied and mundane tasks closer to Earth. But SpaceX’s success in turning its current rocket, the Falcon 9, into the main workhorse for reaching space has made others in the commercial space industry nervous.

“If you’re not careful, SpaceX will be the only game in town,” says Fatih Ozmen, co-founder of Sierra Nevada Corp, a private US company that has been contracted by Nasa to fly cargo to the International Space Station. Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ private space company, makes a blunter claim: SpaceX could end up with “monopolistic control” of US deep space exploration.

Musk’s venture has put itself in a commanding position in the new commercial space industry with surprising speed. It is only 13 years since it became the first private company to launch its own rocket into orbit, breaking into an industry previously dominated by nation states. It has also leapt ahead of contractors such as Boeing and Lockheed Martin, whose joint venture, United Launch Alliance, had carried the flag for US space launch — though using Russian engines.

SpaceX’s ascendancy has been underlined over the past six months by a striking series of wins.

They include a $2.9bn contract awarded by Nasa to use the Starship to land its astronauts on the moon as early as 2024. It was the space agency’s decision to pick only one supplier for this programme, after earlier indicating it would select two, that brought the warning from Blue Origin. Nasa officials point out that they have only awarded SpaceX a single mission, leaving them open to choose other suppliers for future landings. But Blue Origin claims that adapting its systems to work with the Starship will force design changes that will lock the agency into a dependence on SpaceX in the long term.

Musk went on to upstage Bezos a second time late last month. Just weeks before, the Amazon founder and Sir Richard Branson had each made personal trips to the edge of space on their company’s respective rockets. The brief moments they enjoyed in microgravity were eclipsed when SpaceX carried four passengers more than five times higher for a three-day joyride around the Earth, making them the first all-civilian crew to reach space.

SpaceX also announced the first 500,000 orders for its Starlink broadband network, making it the first in a new generation of broadband communications companies operating from a constellation of satellites in low orbit, around 500km above the earth.

And last week, Nasa said two astronauts who had been scheduled to fly on a Boeing spacecraft would be switched to SpaceX’s spaceship instead. The company that defined an earlier era of aerospace has hit too many technical obstacles to carry astronauts on its first commercially developed spaceship, putting it well behind what until recently was just a scrappy start-up.

Rocket science

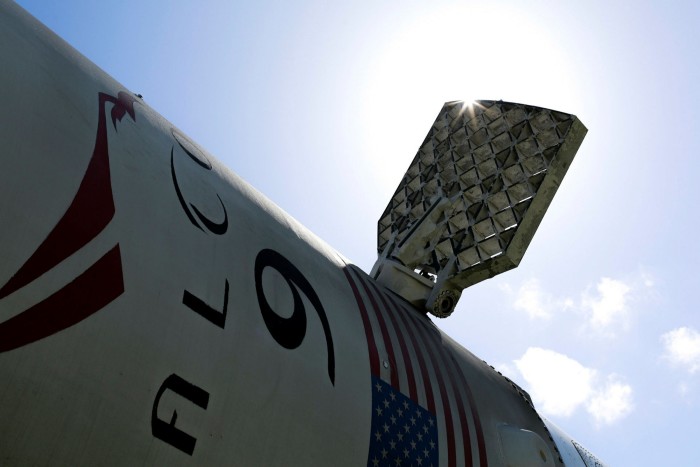

At the heart of SpaceX’s spate of successes is the Falcon 9, which has brought down the cost of reaching space and become a springboard both for the company’s wider business and Musk’s ultimate goal of reaching Mars.

“In terms of performance, cost and reliability, it really is the most successful rocket ever built,” says Diamandis.

SpaceX’s share of the global launch market, excluding China, climbed above 50 per cent for the first time in the first half of 2021, according to BryceTech, a space research and consultancy firm. And while China launched nearly as many rockets as SpaceX in that period, the US company lifted nearly three times as much weight into space.

The tactics that turned the Falcon 9 into the era’s most widely used rocket are now being applied to the Starship. They echo many of the things that also account for the breakout success of Musk’s electric car company, Tesla.

Foremost has been the success of Musk and SpaceX’s CEO, Gwynne Shotwell, at pushing disruptive technologies into mainstream production. In the case of the Falcon 9, that meant using 3D-printing for its engines, the most complex part of the rocket, and reusing the main booster, for future launches.

To master new techniques like these, SpaceX worked on almost every detail of designing and creating its own rockets rather than relying on suppliers, with Musk himself acting as a chief engineer in the early days to goad his team on. SpaceX also took on the full development risk itself, rather than being able to fall back on guaranteed payments from Nasa, forcing much greater financial discipline. As a result, the space agency estimates that the $400m SpaceX spent to develop the Falcon 9 rocket was 10 times lower than the likely cost of a rocket built under traditional government contracting.

Another advantage that SpaceX has shared with Tesla has been its ready access to cheap capital, thanks to the high valuation investors have been prepared to put on its business. Musk has raised more than $6.5bn for the company in the private market, lifting its valuation to $74bn earlier this year. Share sales by some of its investors have since valued it at more than $100bn, according to CNBC.

Most rivals have to generate cash from their existing businesses to fund new ventures, says Steve Collar, chief executive of satellite company SES. The ease with which SpaceX has been able to tap investors has opened the way for it to take much bigger risks, he adds.

One result of the ample cash, along with the company’s access to its own launch service, has been Starlink, which has beaten would-be rivals like OneWeb and Amazon’s Kuiper to launch its broadband service.

Racing to be first has involved technical gambles with its satellite designs, and Starlink is already on its third generation of technology. But even if it ends up writing off billions of dollars’ worth of satellites on the way to perfecting its constellation, the setback would not hurt the company the way it would a rival without access to such cheap capital, says Collar.

Rivals complain that as a result, SpaceX risks squeezing out other companies that haven’t yet achieved its scale and don’t enjoy its funding advantages. Blue Origin, which has lodged a formal complaint over Nasa’s moon landing award, said losing the contract would rob it of one important market for its New Glenn rocket, which has already cost $2.5bn to develop and has yet to leave the launch pad.

SpaceX’s vertically integrated manufacturing approach will also deprive other US suppliers of business, weakening the wider industrial base the country had built up to support its long-term ambitions in space, Amazon and others warn.

However, SpaceX’s customers — including those in government — do not seem to share the misgivings.

“Before SpaceX we only really had the ULA, so we’re in a better position than we were,” says Phil McAlister, director of NASA’s commercial space flight division.

Diamandis goes further: “The US government is lucky to have a company like SpaceX based here,” he says, since its efficiencies feed through directly into the US space programme. And companies that compete with SpaceX in some markets seem more than happy to use its launch services, despite supporting a rival.

“When they came into the [satellite] industry, that freaked people out a bit — but I don’t think it needs to,” says Collar of SES, which is still happy to rely heavily on SpaceX rockets.

Soaring demand

The warnings that a vertically-integrated rocket company could weaken an important supply chain also gets short shrift in many parts of the emerging commercial space industry. Most new rocket companies have adopted a similar model. Jory Bell, a partner at Playground Global, a venture capital firm that has invested in the space industry, also points out that the traditional supply chain has served more of a political purpose than a commercial one. Having suppliers spread across the country has enabled a larger number of politicians to claim success by winning a share of government space contracts.

The most telling argument against the risk of monopoly, though, is that the plunging price of reaching space has brought a boom in demand that is far more than any one company can manage. Much of it is coming from new communications networks aiming to launch constellations comprised of thousands of satellites, as well as more governments eager to reach space for national defence or to take part in deeper space exploration.

“This is a market that will be supply-constrained for many years,” says Edison Yu, an analyst at Deutsche Bank. The space launch market will be worth $37.5bn a year by the end of the decade, he predicted — five times as much in 2021.

That should leave more than enough room for at least one big rival to SpaceX to emerge, according to many in the industry. And even if some existing launch companies struggle, held back by older technologies, uncompetitive manufacturing approaches or cultures built on government contracting, a new generation of disruptive rocket companies is rapidly emerging.

Along with Bezos’ own Blue Origin, they include Relativity Space, a company led by former SpaceX executives, which has raised $1.3bn and plans to make entire rockets using 3D printing, not just the engines.

“We don’t have to beat SpaceX — we just have to beat everyone else,” says Bell at Playground Global, one of Relativity’s financial backers. A generation of engineers and space entrepreneurs trained by SpaceX is helping to build an entire industry based on its ideas, he added.

Satellites and beyond

Starship’s first orbital flight, when it comes, will still reverberate through the space industry. Its sheer scale will change the economics of getting to orbit, setting a new pricing benchmark against which others are likely to be judged.

The Falcon 9 has already brought the price for customers willing to share a launch with others down to $5,000 per kilogramme, around a third of what it was before, says Yu. That price could fall to $1,000, and perhaps even as low as $500, once Starship becomes fully operational, he predicts.

How well adapted it will be for the satellite launches that make up the bread and butter of today’s space industry is another matter. Since Starship will not be able to deposit its large payloads into multiple orbits, the satellites it carries will need their own propulsion to manoeuvre into place, making them considerably more expensive, says Yu.

“You need to get a lot of mass to orbit for some things — and you need speed and agility and precision for other things,” says Dan Hart, chief executive officer of Virgin Orbit, which reached orbit for the first time this year after launching a rocket from under the wing of a Boeing 747.

That is likely to make the Starship “a capability that’s more suited to Mars than commercial satellites”, says Collar at SES.

Some also question how committed SpaceX will be in the coming years to battle for market share in the routine satellite launch business. Falcon 9 was always intended as a stepping stone, to develop the cash flow and the technology needed to carry the company much deeper into space.

Musk should be taken seriously when he muses about turning away from the Falcon 9 and redirecting all of SpaceX’s effort to the Starship and the goal of reaching Mars, according to supporters like Diamandis. “He kills his old products and burns the ship,” he says — one reason he has often succeeded at ambitious new undertakings.

With a lock on today’s launch market, it is probably still far too soon to write the epitaph for the Falcon 9. But when the Starship finally takes to the heavens, it is likely to draw a clear dividing line between one era of space and the next.