Reinhard Krull/EyeEm/Getty Images

If you listen to electric vehicle naysayers, switching to EVs is pointless because even if the cars are vastly more efficient than ones that use internal combustion engines—and they are—that doesn’t take into account the amount of carbon required to build and then scrap them. Well, rest easy because it’s not true. Today in the US market, a medium-sized battery EV already has 60–68 percent lower lifetime carbon emissions than a comparable car with an internal combustion engine. And the gap is only going to increase as we use more renewable electricity.

That finding comes from a white paper (pdf) published by Georg Bieker at the International Council on Clean Transportation. The comprehensive study compares the lifetime carbon emissions, both today and in 2030, of midsized vehicles in Europe, the US, China, and India, across a wide range of powertrain types, including gasoline, diesel, hybrid EVs (HEVs), plug-in hybrid EVs (PHEVs), battery EVs (BEVs), and fuel cell EVs (FCEVs). (The ICCT is the same organization that funded the research into VW Group’s diesel emissions.)

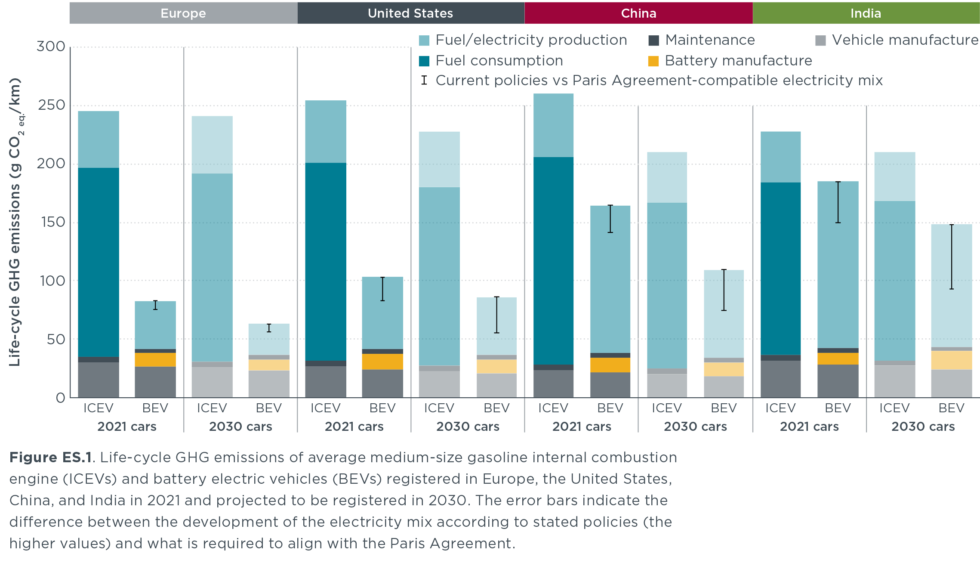

The study takes into account the carbon emissions that result from the various fuels (fossil fuels, biofuels, electricity, hydrogen, and e-fuels), as well as the emissions that result from manufacturing and then recycling or disposing of vehicles and their various components. Bieker has also factored in real-world fuel or energy consumption—something that is especially important when it comes to PHEVs, according to the report. Finally, the study accounts for the fact that energy production should become less carbon-intensive over time, based on stated government objectives.

According to the study, the life cycle emissions of a BEV driving around in Europe today are 66–69 percent lower than a comparable gasoline-powered car. In the US, that range is 60–68 percent less over its lifetime. In China and India, the magnitude is not as great, but even so, a BEV is still cleaner than a fossil-burner. China is at 37–45 percent fewer emissions for BEVs, and India shows 19–34 percent.

Assuming the four regions stick to officially announced decarbonization programs, in 2030 the gap widens in favor of BEVs, even accounting for more efficient engine technologies and fuel production. In Europe, the gap is predicted to be 74–77 percent; in the US, 62–76 percent; in China, 48–64 percent; and in India, 30–56 percent. Bieker writes that the wide spread is due to “a large uncertainty… in how the future electricity mix develops in each region.”

ICCT

There’s some good news for hydrogen hounds in the paper, too. Although FCEVs are currently only abut 26–40 percent less carbon-intensive than a comparable gasoline vehicle, if hydrogen was produced using renewable energy rather than steam reformation of natural gas, that number would jump to 76–80 percent, even better than a BEV’s numbers.

But Bieker’s analysis says that there is no future for internal combustion engine vehicles if we are to actually decarbonize. HEVs only reduce lifecycle emissions by about 20 percent, and PHEVs are little better in Europe (25–27 percent lower than gasoline), a little worse in China (6–12 percent lower than gasoline), and adequate in the US (42–46 percent lower than gasoline). But compared to BEVs, a PHEV will have much greater lifetime emissions in all three areas. (India has almost no PHEVs, apparently.) And the advantage of BEVs over HEVs and PHEVs only grows as the grid decarbonizes more.

Even the introduction of biofuels will not help the internal combustion engine stay relevant, and Bieker writes that “the registration of new combustion engine vehicles should be phased out in the 2030–2035 time frame” if we want to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement. Last September, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order setting 2035 as the date that all new vehicles sold in the state must be zero-emissions vehicles.