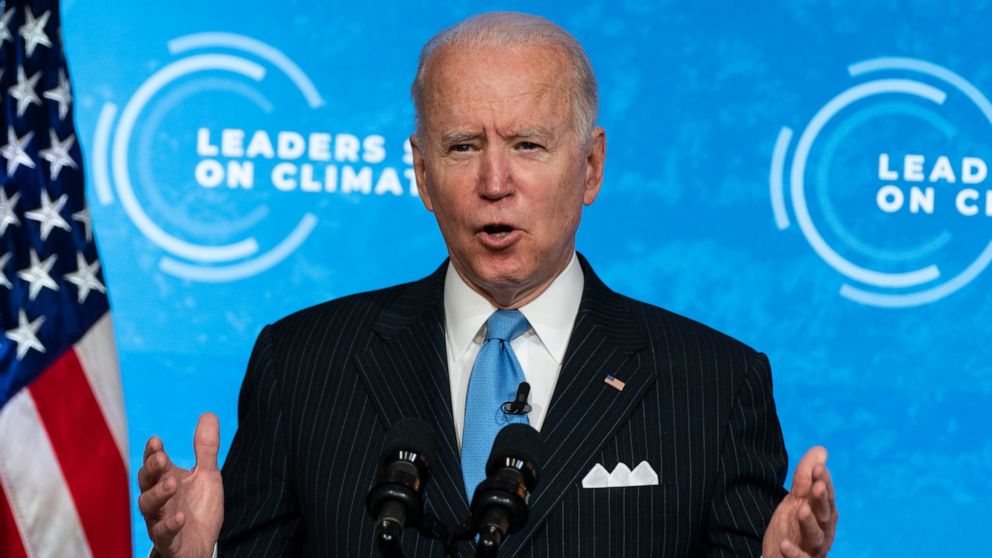

DETROIT (AP) — For President Joe Biden to reach his ambitious goal of slashing America’s greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, huge reductions would have to come from somewhere other than one of the worst culprits: auto tailpipes.

That’s because there are just too many gas-powered passenger vehicles in the United States — roughly 279 million — to replace them in less than a decade, experts say. In a typical year, automakers sell about 17 million vehicles nationwide. Even if every one of the new ones were electric, it would take more than 16 years to replace the whole fleet.

What’s more, vehicles now remain on America’s roads for an average of nearly 12 years before they’re scrapped, which means that gas-fueled vehicles will predominate for many years to come.

“We’re not going to be able to meet the target with new-car sales only,” said Aakash Arora, a managing director with Boston Consulting Group and an author of a study on electric vehicle adoption. “The fleet is too big.”

So unless government incentives could somehow persuade a majority of Americans to scrap their cars and trucks and buy electric vehicles, reducing tailpipe emissions by anything close to 50% would take far longer than the Biden timetable. Last year, fewer than 2% of new vehicles sold in the United States were fully electric.

“If every new vehicle sold today was an electric vehicle and it was entirely powered by renewable energy overnight, it would take 10 years or more for us to achieve a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions,” said Chris Atkinson, a professor of mechanical engineering and director of smart mobility at Ohio State University.

Which means that other sectors of the economy would have to slash greenhouse gas emissions deeply enough to make up the shortfall in the auto industry.

Transportation as a whole, which includes not only cars and trucks but also ships and airplanes, is the single largest source of such pollution. Of the nearly 6.6 million metric tons of carbon dioxide that were emitted in the United States in 2019, transportation produced 29%. Next was electricity generation at 25%. Then came factories at 23%, commercial and residential buildings at 13% and agriculture at 10%.

Electricity generation is the most likely source of faster reductions. That sector has already made major strides. Last year, carbon emissions from electricity generation were 52% lower than the government had projected they would be in 2005, according to government’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The reasons: more use of natural gas, solar and wind power, as well as reduced demand as the economy has evolved to achieve gains in energy efficiency.

Biden, who unveiled his goals at a climate summit with world leaders Thursday, has yet to detail the greenhouse gas reductions that his administration envisions for each sector of the economy. Overall, the reductions are intended to limit global warming as part of the president’s vision of a nation that produces cutting-edge batteries and electric cars, a more efficient electrical grid and caps abandoned oil rigs and coal mines.

Gina McCarthy, Biden’s top climate adviser, appeared to signal Thursday that deeper cuts in emissions would have to come from sectors other than the auto industry to reach the goals. She defended the administration’s decision not to set a specific deadline for ending sales of new gas-powered cars or for achieving net-zero emissions from the transportation sector.

“We have a whole lot of ways” to cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in half without a transportation goal, McCarthy said.

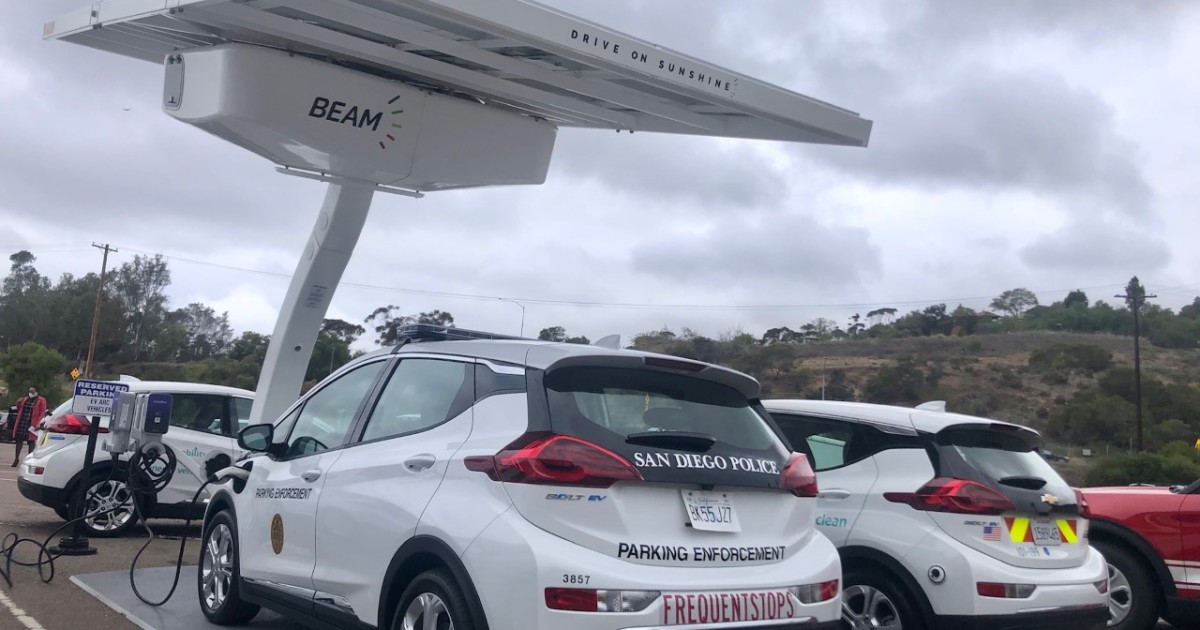

For the transportation sector, the government says it will improve vehicle efficiency, invest in low-carbon renewable fuels and produce transit, rail and bicycling improvements. The administration also wants to convert the 650,000-vehicle federal vehicle fleet to battery power.

To increase sales of electric vehicles, the administration plans to spend $15 billion to build a half-million charging stations by 2030, as well as offer unspecified tax credits and rebates to cut the cost.

Swapping the entire fleet of gas burners for electric vehicles could take even longer than 20 years. Todd Campau, associate director of automotive for IHS Markit, estimates that the number of mostly gas-powered vehicles on U.S. roads, will keep growing — to 284 million by 2025.

“The situation is only getting worse as far as the volume that needs to be exchanged,” Campau said.

He and others say it would take highly attractive government incentives to lure additional people out of their gas-burners — something like a reprise of the 2009 cash-for-clunkers program proposed by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York, but on a vastly larger scale. The Schumer plan proposes rebates of at least $3,000 for people to scrap combustion vehicles for electrics.

Bill Hare, director of Climate Analytics, a Berlin-based climate think tank, predicted that pollution reductions in the transportation sector will come after 2030 as the electric vehicle fleet grows.

“What you would then end up seeing is more or less complete decarbonization of the transport sector — but by 2050,” he said.

Even if tailpipe emissions can’t be cut quickly, Biden’s goals can be reached with significant cuts in electric powerplant emissions as well as reductions in methane pollution from oil wells and cuts in hydrofluorocarbons used in refrigeration and air conditioning, said Kate Larsen, director at Rhodium Group, a research firm. Studies show that electric power emissions can be cut 80% by 2030 with a mix of investment and regulations, Larsen said.

“That will get us the bulk of the way,” she said. “We won’t see 50% reductions across the board.”

Zero emissions electric generation sets the stage for converting cars and many other pollution sources to electricity, she said.

Even countries that are ahead of the U.S. in electric vehicle adoption, mainly in Europe and China, estimates are that sales still won’t put enough electric vehicles in use to reach 2030 carbon dioxide reduction goals, according to a Boston Consulting report. In Europe, which has strong incentives and strict pollution limits, the market share of battery-only and plug-in hybrids jumped from 3% to 10.5% last year. That’s far from enough.

“If half of new cars sold around the world in 2035 are zero-emission vehicles, 70% of the vehicles on roads will still be burning gasoline or diesel,” the report said.

Faster adoption could be limited, too, by a lack of factory capacity to make batteries. The U.S., for instance, has only four plants that are either built or in the works. It would need 50 to electrify the entire fleet, said OSU’s Atkinson.

Even so, a switch from internal combustion to electric vehicles is well under way, and Boston Consulting says it will accelerate. The company foresees new plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicle sales rising from 12% of the global market in 2020 to 47% in 2025. It notes that battery costs are falling and automakers plan to introduce 300 new EV models by 2023, giving consumers a huge array of choices.

“There’s a path for this to move quite quickly,” said Nathan Niese, an author of the Boston Consulting report. “Business is moving in that direction. The government can just be the accelerator on top of that.”