Cotton and soyabeans grow in the west Tennessee fields where, in four years, Ford Motor plans to manufacture electric trucks.

Last month Ford and its partner SK Innovation said they would invest $11bn to construct an electric vehicle assembly plant, battery factory and supplier park on the farmland 50 miles north-east of Memphis, plus two battery plants in neighbouring Kentucky.

The billions of dollars to be invested highlight the economic stakes for communities as the automotive industry commits to massive spending to switch away from assembling petrol-power vehicles.

US towns, states and regions are vying to lure new electric vehicle plants. Ford’s Tennessee complex, to be dubbed Blue Oval City, will rise in an area that Haywood County mayor David Livingston said had been haemorrhaging population since the second world war.

“EVs are the wave of the future,” Livingston said. “I felt like I was on third base in the 1960 World Series when Bill Mazeroski hit a grand slam, that’s how ecstatic I am.”

The car industry is critical to the US economy. It accounted for 3 per cent of US gross domestic product last year and employed more than 900,000 people in manufacturing vehicles and parts with another 200,000 in sales. Average annual pay totals $84,000, $20,000 more than the average for all US industries.

But the spoils are not evenly distributed. Carmakers and their supply chains have historically been clustered in the Midwest, starting with Henry Ford cranking out Model Ts in south-east Michigan.

The economic benefits began to spread more widely in the 1970s and 1980s as US carmakers opened factories in southern states. Japanese and German carmakers followed suit. Today Kentucky, Tennessee and Alabama — the southern sections of an “auto alley” that runs from Michigan — all boast healthy car manufacturing sectors.

With electrification now rolling across the industry, cities and states are competing to either preserve their share of the economic benefits — or win a bigger piece of the pie. A Michigan council formed by Governor Gretchen Whitmer said in a 2020 report that while the state remained a global leader in electric and autonomous vehicle technology, “the margin of our lead has been closing”.

Detroit’s title of “Motor City” is one that rivals would love to steal. Tennessee offered Ford $500m in incentives, while Kentucky officials expect the company to apply for $286m in forgivable loans and skills training. And the states that lost out on Ford’s new factories are “soul searching” right now, said Brett Smith, technology director at the Center for Automotive Research, or CAR.

“Those were two very, very large investments,” he said, referring to the sites in Tennessee and Kentucky. “They’re hard to go to your boss and say, ‘Hey, we weren’t in the game.’ And there were several that weren’t in the game.”

Ford’s decision will bring to four the number of plants building electric vehicles in Tennessee. Nissan has manufactured its Leaf car there since 2017, Volkswagen plans to make the ID. 4 electric sport utility vehicle in Chattanooga and General Motors said last year it would spend $2bn to retool its Spring Hill plant for EVs.

Kristin Dziczek, the CAR’s senior vice-president of research, said that carmakers’ location calculations appeared to be “that they have land, decent costs, their workforce and their supply chain” as they decided where to build EVs.

Large, “shovel-ready” sites are important. A group of Tennessee officials from the public and private sectors began piecing together the 4,200-acre “mega site” that Ford eventually chose almost two decades ago, buying up land from 26 owners.

Lisa Drake, Ford’s chief operating officer for North America, said the company selected Tennessee and Kentucky because of their proximity to other Ford factories and suppliers, access to sustainable energy and lower construction and operating expenses, which “are very critical . . . to keep battery cell costs low”.

Electricity is a “significant” cost to manufacture EV batteries, although it is dwarfed by the cost for both labour and rare earths, said Gregory Keoleian, director of the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems.

Electricity for industry costs 7.2 cents a kilowatt-hour in Michigan, compared to about 5.3 cents in both Kentucky and Tennessee, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The federally-owned Tennessee Valley Authority generates a majority of the state’s power using nuclear and hydro resources, a draw for carmakers wanting to cut emissions from manufacturing processes along with their products.

Industry observers note the TVA, established during the Great Depression to control flooding and electrify rural communities, has given Tennessee an edge in other ways. Several years ago authority officials began courting overseas battery makers. Now, in a state that in 2018 had fewer than one electric vehicle registration for every 1,000 people, they are helping to build a network of fast-charging stations every 50 miles along the state’s big highways.

“That just says really good things to manufacturers,” said Kim Hill, president of the consultancy HWA Analytics.

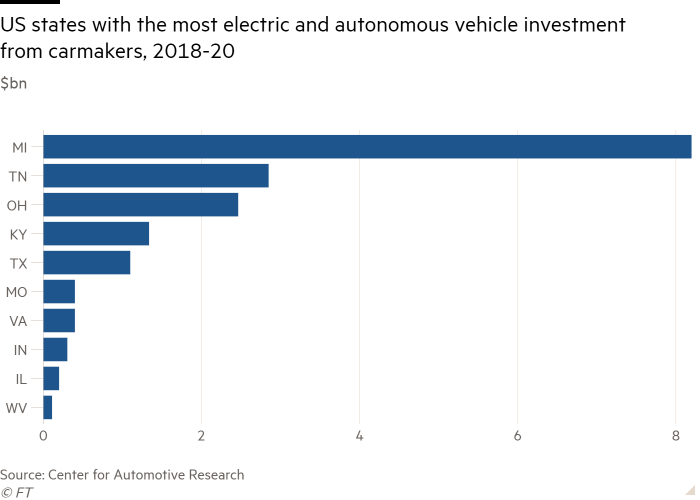

But headline-grabbing greenfield investments such as Ford’s obscure just how much companies have spent to update their longstanding Midwestern bastions for electric vehicles. CAR data show that between 2018 and 2020, carmakers invested more than $8bn in Michigan in EVs and autonomous vehicles, while Ohio received $2.5bn and Indiana $304m.

The CAR estimates that by the end of the decade the northern Midwest will manufacture a significant chunk of America’s electric vehicles with three states — Michigan, Ohio and Indiana — sending out 30 per cent of them. While the US South will produce 45 per cent of EVs, that manufacturing footprint will cover eight states.

Meanwhile, the mayor of Haywood County, Tennessee is making plans for new water and sewer lines to serve the Ford complex and the businesses and residents expected to spring up around it.

“It’s almost inconceivable to most of the locals exactly what’s going to happen,” Livingston said. “I tell them Detroit has moved to west Tennessee.”